CENTER CITY

© Helene Schenck & Michael

Parrington, Workshop of the World (Oliver Evans Press,

1990).

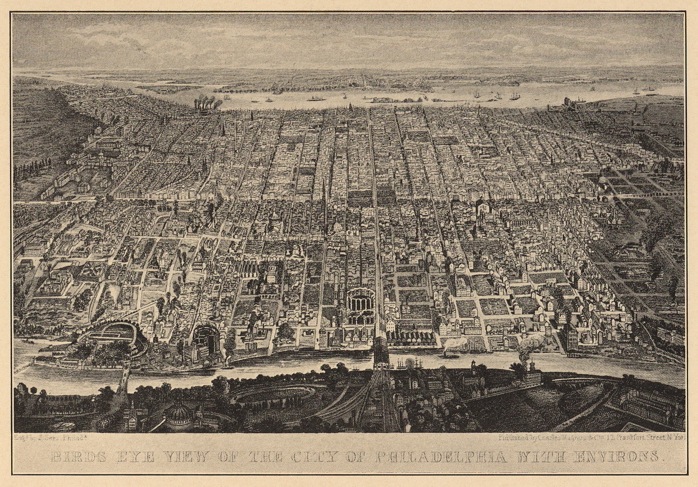

Until 1854, the City of

Philadelphia encompassed an area of 2,277 square miles

bounded by the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers to the east

and west, and by Vine and South Streets to the north and

south. This area, laid out by Penn's surveyor Thomas

Holme in the 1680s, forms the focus of this section of

the guidebook.

The city first developed along the Delaware riverfront,

although Penn envisaged a city stretching from the

Delaware River to the Schuylkill River. Throughout most

of the eighteenth century, the city clustered east of 6th

Street and stretched north and south in a linear fashion

into the Northern Liberties and Southwark. This area saw

the majority of the eighteenth century industrial

development of the city.

By the early nineteenth century, development had reached

Center Square and continued westward to the Schuylkill

and into West Philadelphia. By the middle of the

nineteenth century, Philadelphia had spread far beyond

the confines demarcated by Penn, and the Consolidation of

1854 recognized this fact by enlarging the city

boundaries to match those of Philadelphia County.

Early houses in the seventeenth century city were of log

construction, but by 1683, a brickworks was in operation

north of the city. One of the earliest brick houses was

constructed at the south corner of Front and Mulberry

(now Arch) Streets in 1684. By the end of the seventeenth

century, there were three brewhouses in the town, a

ropewalk, four shipyards, and numerous wharves and

warehouses. Businesses and industries utilized the

services of sawyers, brickmakers, dyers, shoemakers,

brewers, maltsters, coopers, and potters, to name but a

few of the 35 trades documented in the seventeenth

century city in research conducted by Hannah Benner

Roach. 1

Dock Creek was the site of much of the early industry

which required a water source. Numerous tanners set up on

the banks, and by the mid-eighteenth century, many

complaints were voiced about the noisome conditions of

the water course. As the city developed during the

eighteenth century, polluting activities like tanning,

potting, and brickmaking moved out to the outskirts of

the residential area. Potters like Antony Duche, who

operated a kiln on Chestnut Street not far from the State

House in the 1760s, found themselves persona non grata.

Increasingly, the less socially acceptable

industries were pushed out to the Northern Liberties, and

west to the Schuylkill River.

Many industries continued to operate in Old City but they

tended to be relatively small scale in comparison to

entities like the Baldwin Locomotive Works and the

Disston Saw Works. Larger industries did congregate along

the Schuylkill riverfront, and by the nineteenth century

there were many wharves and landings in use by these

concerns. Many of these industries had started

their existence in Old City and as land prices increased,

they gradually moved westward. Typical of these was the

Wetherill Paint and Chemical Company, which commenced as

a textile concern in Old City in 1775. The company

branched out into hardware and paints and dyes, and by

1809, appears to have been manufacturing white lead at 19

S. Seventh Street. Shortly after this, a new factory was

erected at Twelfth and Cherry Streets. The company

operated at this location successfully until 1848 when a

new facility was opened on the west bank of the

Schuylkill between Chestnut and Walnut Streets.

2

By the mid-nineteenth century, a pattern had emerged of

smaller industries interspersed with domestic housing

throughout much of Old City and Center City. Along the

Delaware riverfront south of Market Street, there were

numerous piers and warehouses where products were stored

prior to shipment or after importation. On the Schuylkill

riverfront, wharves and storage facilities served the

internal commerce of Pennsylvania via the Schuylkill,

Delaware, Lehigh, and Main-Line Canals.

3

The demise of the canal system and the rise of the

railroads transformed the built environment of

Philadelphia as the lines of the Pennsylvania,

Philadelphia & Reading, and Baltimore & Ohio

Railroads edged into the city on soaring viaducts and at

grade level.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, a survey

conducted by the city 4

provided a

revealing picture of industry in Philadelphia. In 1882,

there was a total of 4,062 manufacturing establishments

in the area defined by South and Vine Streets, and the

Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, employing 91,728 people,

with a product valued at over 236 million dollars.

Industries employing more than 1,000 people

included bookbinding, boot and shoe manufacturing,

clothing, confectionery, furniture, gas works, hosiery,

iron working, paper boxes, printing, silk manufacturers,

and umbrella making. Clothing was by far the most

important industry, with finished goods valued at over 36

million dollars. This was followed by boot and shoe

manufacturing at over 9 million, and sugar refining at a

little under 6 million. Although sugar refining ranked

third in terms of product value, it employed

comparatively few people—315 in two establishments.

Clothing employed 25,671, and boot and shoe manufacturing

7,567: accounting together for over 36% of the total

working population of the area.

In the twentieth century, clothing continued to be an

important industry and many of the loft buildings still

to be seen in Old City and Center City at the present

time originated as sweat shops producing clothing. Much

of the industry along the Delaware waterfront, including

the two sugar refineries, was removed when the Delaware

Expressway was constructed in the 1970s. Many of the

nineteenth century industrial buildings of Philadelphia,

however, still exist in the area bounded by the two

rivers and Vine and South Streets. These structures

largely have survived by being adapted and reused as

offices and apartment buildings, serving the needs of

Philadelphia's service-oriented population of the 1980s.

For the most part, the interiors of these buildings have

been gutted and only the facades survive to remind the

visitor of Philadelphia's industrial

past.

1 Russell F. Weigley,

editor, Philadelphia:

A 300-Year History, p. 20.

2 Miriam Hussey,

From

Merchants to "Colour Men": Five Generations of Samuel

Wetherill's White Lead Business (1956).

3 Baist, 1895.

4 Lorin Blodget,

Census

of Manufactures of Philadelphia, (Philadelphia, 1883), pp.

8-44

Resources:

Center City

bibliography