© Philadelphia Year Book, 1917.

PORT RICHMOND & BRIDESBURG

© Jack J. Steelman,

Workshop of the

World (Oliver Evans Press, 1990).

There are at least two

versions of how Bridesburg got its name. The first

centers on Joseph Kirkbride who settled in the area in

1801. As the operator and owner of the bridge across the

Frankford Creek, Kirkbride accumulated enough money to

purchase large tracts of land in what was then called

Point No Point. The name of the area soon became

Kirkbridesburg, the burg coming from the German ethnic

character of the community. As this version of the story

goes it was shortened to Bridesburg.

A second version rests on the tradition in the Frankford

Community of brides going to the river community for what

today would be called a "honeymoon." Some local residents

insist that the name Bridesburg came from this practice.

Whether the folklore is true or the Kirkbride story is

true bears little on the settlement of the community.

The original inhabitants of Bridesburg were the Lenni

Lenape Indians. In 1643, Swedes, led by Johanne Printz

settled in Bridesburg. A vision of the river ending

impressed these early settlers—thus the name Point

No Point." In the 1660s, more immigrants came and

received "Liberty Grants" from William Penn. These were

free grants of 80 acres given to anyone who purchased

5000 acres of land in Pennsylvania. The Swedes were soon

outnumbered by the German Catholics. In 1664 Penn

accepted the Swedes' offer to trade this land in Point No

Point for land in Conshohocken. Throughout these early

years Bridesburg was the river port for Frankford. Bridge

Street became the main road to the Bridesburg wharf. The

opening of the Frankford Arsenal in 1812 further

increased population and established Bridesburg as a busy

river stop.

Joseph Kirkbride was aided in his settlement of

Bridesburg by Alfred Jenks. In 1820 he established the

Bridesburg Manufacturing Company, a textile mill along

the Frankford Creek. The limited water flow of the creek

did not permit enlargement of the textile industry in

Bridesburg. A more important and lasting effect on the

neighborhood was the opening of the Tacony Chemical Works

in 1842. Founded by Frederick Lennig in 1819 the firm

attracted a large number of workers from Germany,

establishing that population as the dominant nationality

in early Bridesburg.

The major influx of the Polish population occurred

between 1900 and 1920. The Frankford leather plant of

Robert H. Foerderer Inc. originally hired Polish men to

work in curing the hides. This process consisted of

soaking hides for days in dog manure to soften it. The

smell of the manure and the need to handle the soaked

leather made this job unacceptable to most Philadelphia

workers. However, the new Polish immigrant, excluded from

most factory work in the city, flocked to Bridesburg for

work. Many of these men had come to America to seek their

fortune, hoping to return to their native Poland.

Unfortunately, World War I intervened and the Polish men

of Bridesburg could not return home, lest they be

arrested and imprisoned for 20 years as draft dodgers

under a law enacted during the war. With the end of the

war many Polish women migrated to join the men of the

town. This rapidly changed the ethnic character of the

Bridesburg from German to Polish.

© Philadelphia

Year Book, 1917.

In 1894 the opening of the first trolley line in the

northeast connected Frankford, Bridesburg, Tacony, and

Holmesburg along State Road. Nicknamed the Hop, Toad, and

Frog Line it was used by many workers in Bridesburg.

Residents now had a chance to work at Henry Disston and

Sons Saw Works and Erben Search textile mill in Tacony,

and the Foerderer Leather Works near Frankford. Such

travel was so widespread that it was general knowledge in

Tacony that Polish women from Bridesburg made up half of

the Erben Search workforce.

In 1920 the Lennig Company was bought out by Rohm and

Haas, an already established chemical company. Haas had

come to America in 1906 bringing with him a new chemical,

Oropon, for curing leather. Acceptance of this chemical

by Foerderer initiated the opening of a Rohm and Haas

plant nearby and eventually in Bristol, Bucks County.

Rohm remained in Germany manufacturing the same chemical

for European use. This gave the company an international

flavor. The company stayed relatively small until World

War II when it developed a synthetic chemical which

produced plexiglas for fighters and bombers. It was this

discovery which catapulted Rohm and Haas into the

position as a world leader in chemical production.

Today Bridesburg is a community with several strong

social and service organizations. With endowments from

Rohm and Haas, the Civic Association of Bridesburg was

able to build the Boys and Girls Club in 1941. The Club

has conducted sports and other recreational activities

for the children of the community since that date.

Bridesburg is also a patriotic town. There are two

American Legion Posts, and a Veterans of Foreign Wars

Club, they oversee memorials saluting Bridesburg

veterans. Other institutions that play an important role

in preserving Bridesburg's history include churches of

various denominations, the Bridesburg Businessmen's

Association, and the Frankford Historical Society.

Although Bridesburg is located within a large urban area,

its atmosphere remains that of a small town community.

Located between the Delaware River and the Frankford

Creek its boundaries have changed little over the years.

Despite the closing of the Frankford Arsenal, Erben

Search Inc., Henry Disston and Sons, and Foerderer

Leather Works, Bridesburg remains an active industrial

community. It is the home of workers for Allied Chemical

Company and Rohm and Haas. Today Bridesburg remains one

of the largest Polish communities in Philadelphia.

©

Philadelphia Year Book, 1917.

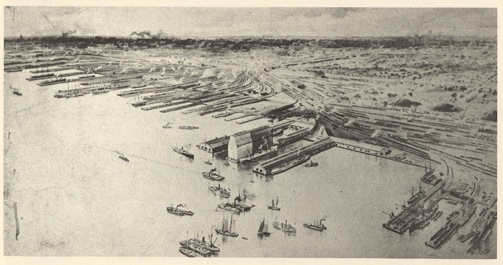

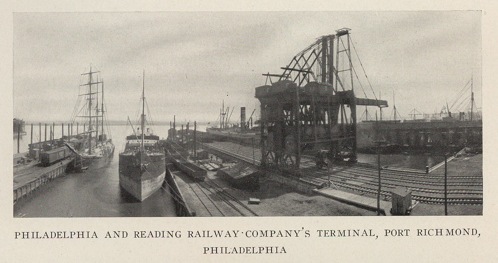

The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad completed its

trackage from the banks of the Schuylkill to the banks of

the Delaware in 1842 and shortly thereafter, in 1847, the

Richmond district was formed. 1

"Sketch map of Phila. and Readg. Rail Road

and its branches" (1873), terminating in Port

Richmond.

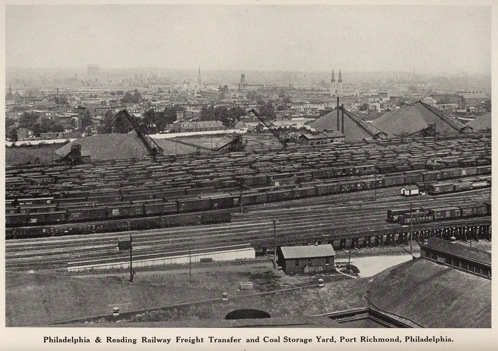

Most of the early growth of the area resulted from

development of the Port Richmond freight handling

facilities of the Reading; from the time of its early

construction until its dismantling in 1976, the Port

Richmond yards and docks constituted the largest

privately-owned tidewater terminal in the world, covering

over 230 acres. At one time, the piers received and

discharged cargoes destined to ports around the world as

well as to the Atlantic coastal trade. The freight and

coal storage yards west to Front Street had a capacity of

approximately 5,600 cars (based on 44' car lengths).

©

Philadelphia Year Book, 1917.

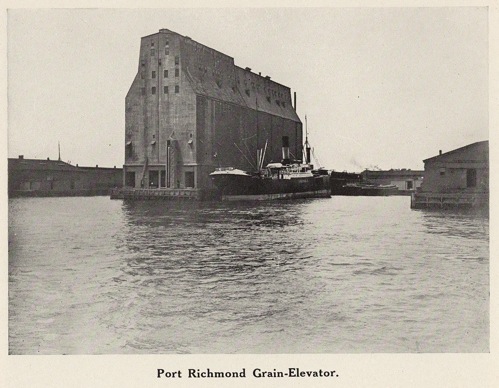

The

2.5 million bushel grain elevator, c.1928, was converted

to coal handling after Conrail took over operations;

ships were loaded at a rate of 25 million bushels per

hour, which translated to over 27 million bushels in a

single year. Pier 18, the Coal Dumper, built in 1918 (now

demolished), could unload one 55-70 ton car every two

minutes. Next upriver was Pier 14, the Ore Facility,

which had an unloading capacity of 400 tons per hour and

annually handled more than 1 million tons of imported

ore.

© Philadelphia

Year Book, 1917.

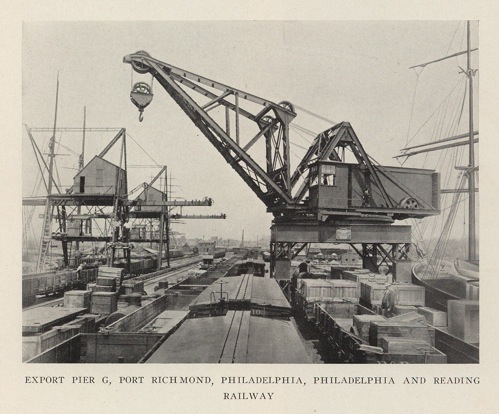

Another important

facility in the Terminal was the 100-ton Dock Crane,

located on Pier G; it was one of the largest on the

Atlantic Seaboard. The last pier in the terminal, located

near the Allegheny Avenue end, was Pier J, which

consisted of four car floats, each equipped to handle up

to five cars, that once moved over 100,000 cars per year

to New Jersey customers.

© Philadelphia

Year Book, 1917.

Coal was handled

primarily in the southern end of the facility. In this

area, a large shed containing five tracks, each capable

of handling six to eight cars, was constructed for

wintertime loading. The shed contained steam coils to

thaw frozen carloads of coal so that they could be dumped

into ships. Coal dumping was accomplished by one of two

means:

1. By electrically-powered "mules" which ran on

narrow-gauge tracks (between the standard gauge rails)

that hoisted the loaded cars, one at a time, up to a

rotating platform. Once positioned on the platform, the

wheels of the loaded car were locked onto the track and

the platform, with the car firmly secured, was flipped

over by steam-powered winches and the contents emptied

onto an apron that fed the falling coal into the hold of

the waiting ship. After the platform and car were

righted, the car was released to coast back into the yard

and the next one was shuttled into place by the mule.

2. The use of chutes placed on pier tracks that guided

the coal, which was systematically emptied from the

bottoms of the hopper cars, into the holds of the ships.

Obviously, the first method was faster, and certainly

much more dramatic.

Grain, raw sugar, and bulk

materials were also stored and handled at the Port

Richmond facilities. Interestingly, in the center of the

terminal was a small chapel, staffed by the Church of the

Assumption on Allegheny Avenue. It was originally

established so that merchant seamen would have a place to

worship that was close to their ship; however, it also

became a popular place for some of the neighborhood

families as it was close for them, too.

© Philadelphia

Year Book, 1917.

Since the closing

of the terminal in 1976, much of the trackage and piers

have been removed; the site now sits idle.

1 Richard Webster,

Philadelphia

Preserved, (Philadelphia, 1976), pp.

305 & 312.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Dr.

Harry Silcox, who prepared much of the overview

information on Bridesburg. Thanks also to John R. Bowie,

who assisted in the preparation of the material on the

sites. Thanks also to Frank Weer,

who contributed considerable information on the Port

Richmond facilities.

Resources:

Port Richmond - Bridesburg

bibliography