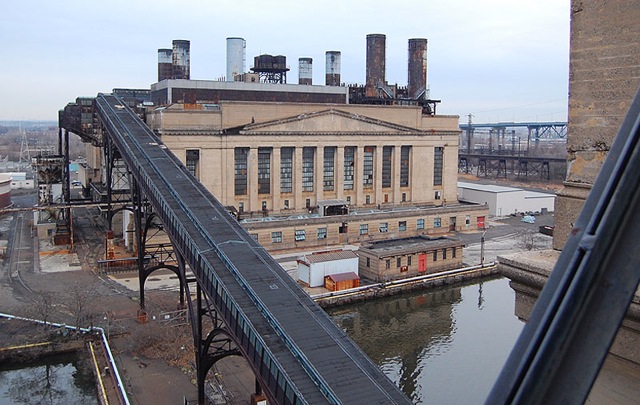

—"View from the coal tower over the Delaware," Ethan A. Wallace, photographer (© 2007)

Richmond Generating Station, 1925

Delaware Avenue and Lewis Street, Philadelphia PA 19137

© Jack J. Steelman,

Workshop of the

World (Oliver Evans Press, 1990).

The population increase in

the northeast section of the city in the early 1920s gave

rise to the need for an increase in Philadelphia

Electric's generating capability. At that time, the

Schuylkill and Delaware Generating Stations were the only

plants in the city, with the exception of the small and

outmoded Tacony Station adjacent to the Lardner's Point

Pumping Station. So the decision to construct a new

facility in Richmond was easily made.

As designed, the station was to contain three distinct

generating components; each component was to consist of a

boiler house to produce steam, a turbine hall, and a

switch gear building to control power distribution.

Generating steam pressure was designed to be 400 psi

instead of the customary 100 to 125 psi. Each of the

three turbine halls was designed to contain four tandem

compound turbo-generators that would ultimately each

produce 50 MW of power at 13.2 kV, for a total capacity

of 600 MW. Each boiler house was designed to contain 24

Babcock & Wilcox stoker-fired boilers.

—"Turbine

Hall" is but one of 35 black & white photographs of

Richmond Generating Station taken for HAER in

2000 by Joseph E. B.

Elliott.

Only one of the three generating components was

constructed. Turbine Hall was one of the largest open

rooms ever designed, modelled after the ancient Roman

baths. Two of its four turbo-generator units were

installed and twelve of its 24 planned boilers were put

into place. The plant operated for ten years in this

manner; lack of anticipated power demands plus the

construction of the Conowingo Hydroelectric Facility on

the Susquehanna River in northeastern Maryland made

additional equipment and generating capability

unnecessary.

In 1935, a third unit rated at 165 MW (by Westinghouse)

was installed; it was powered by two pulverized

coal-fired boilers that gave it an effective rating of

135 MW. After World War II, it was overhauled and two new

stoker-type boilers were added; this extra bit of power

pushed the generating capability of the unit up to full

capacity.

In 1951, a fourth unit, rated at 185 MW was added; it ran

at a steam pressure of 1200 psi (as opposed to 400 psi).

Also, it was hydrogen-cooled instead of air-cooled like

the other units.

Water feed requirements of the high pressure boilers

necessitated a demand for extremely pure water. As the

water was taken directly from the Delaware River, a new

set of system evaporators was added. In this system water

was passed through strainers and filters; then was

softened, evaporated, and condensed at a rate of 50,000

pounds of water per hour.

—"Looking down upon a

turbine," Ethan A. Wallace, photographer

(©

2007)

In the late 1960s, power demand from the burgeoning

northeast necessitated the installation of a series of

nineteen combustion jet-type turbo generator units at

Richmond. Eight of these units were built by Westinghouse

and rated at 25 MW each. Eight were built by Worthington

and consisted of two Pratt & Whitney jet engines

(similar in design to a 707 jet engine). These engines

were positioned back-to-back so that their exhausts were

directed into turbine casings that were attached to

generators capable of producing 40 MW each. The final

three units were heavy duty combustion turbines by

General Electric and rated at 60 MW each.

Richmond supplied power on four levels: the first was at

13.8 kV for large plant use such as the Sears Roebuck

plant or the Frankford Arsenal; the second level was 220

kV for large substations in the area as well as the

regional power grid; the third was 66 kV for nearby

substations; and the fourth level was for the

railroads—60 cycle, three-phase power was converted

to 25 cycle, single-phase power for the Northeast

Corridor.

The steam plant was shut down in 1984; all of the jet

units have been sold except for two of the GE units which

are still used during times of peak load. The switchyard

is still live. Presently, the metal in the plant is being

harvested for scrap and the asbestos is being removed.

Otherwise, the plant sits idle except during periods of

high demand.

—"Coal conveyor", Joseph E. B.

Elliott (2000).

Update

December 2007 (by Ethan A. Wallace,

photographer):

—Turbine Hall,

Ethan A. Wallace, photographer

(© 2007)

Approaching the main gate

from the North, the only sign that Richmond Generating

Station is still used at all is the light coming from the

windows of some of the small outer buildings. The

asbestos removal, one of the largest asbestos abatements

ever, has long been complete. Otherwise the place has

changed very little. Tools can still be found where they

were left; huge machines sit idle. Only the darkness and

the rust betrays how long this place has sat unused.

Some areas, such as the great domed turbine hall and the

long conveyor from the coal tower to the plant have holes

in the ceiling and missing windows. Moss grows on

permanently damp floors and rust threatens to eat through

gratings that make up much of the upper floors. The roof

still reveals copper trim around all the skylights and

windows, despite the fact the scrappers have begun to

loot the building for anything of value. From the roof as

well as through numerous missing windows you can hear the

electric buzz of the still active switch yard on the

plant’s south side.

The oddest things in Richmond have nothing to do with its

original functions. The building was one of the locations

used for the movie Twelve Monkeys and artifacts for the

film can still be found throughout the structure. Doors

bear false names such as The Bunker, or Infirmary, cans

of paint labeled after the set they were for sit in the

halls. In one spot there was a pile of old x-rays, some

bearing the legend Pennhurst State School on the bottoms.

In the midst of one room is a plywood wall with a window

and what appears to be the front of an MRI machine

connected perpendicular to it.

While the fate of Richmond is not clear, there is an

immediate threat to this historical and beautiful

building. Sawn-off pipes and missing trim stand as

evidence of scrapping activity in the plant. In fact

while we were photographing the turbine hall from the

upper level, two scrappers entered down by the turbines

and proceeded to saw off and remove some of the

pipes.

-----

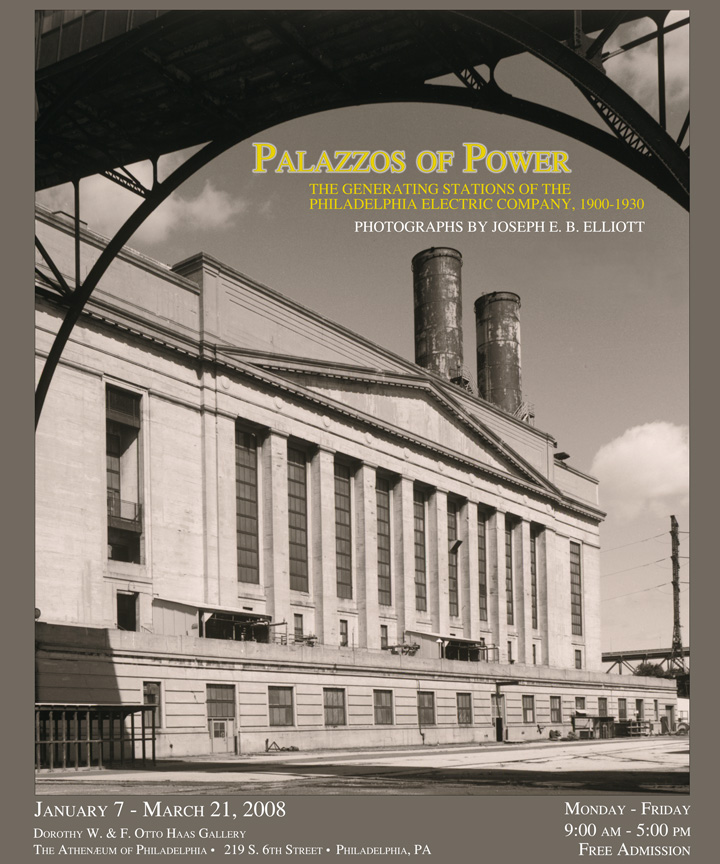

—Palazzos of Power exhibit

details.