KENSINGTON

© Carmen A. Weber, Irving

Kosmin, and Muriel Kirkpatrick, Workshop of the World (Oliver

Evans Press, 1990).

As the area north and west of

Fishtown developed in the 1840s, the old neighborhood

name "Kensington" spread as well. Today, Kensington forms

an upside down, L-shaped neighborhood around Fishtown,

bounded by Erie Avenue on the north, 6th Street and

Germantown Avenue on the west, Girard Avenue on the

south, and Frankford Avenue, Norris Street, and Aramingo

Avenue on the east.

Traditionally, Kensington was known as the original hub

of working class Philadelphia, with both native and

immigrant workers living close to their work sites or

working at home. Early nineteenth century industry in the

area was diverse; it included glass factories and

potteries, wagon and machine works, and a chemical

factory. Many of the earlier sites were located in West

Kensington (west of Front Street), spreading north from

the Spring Garden District and Northern Liberties.

However, the textile trades came to dominate Kensington

by the mid-nineteenth century. The genesis of the ingrain

carpet industry was centered around Oxford and Howard

Streets in West Kensington, 1

where some mills

still stand. Other early carpet mills in this area are

now gone, but they included James Gay's Park Carpet Mill,

the Dornan Brothers' Monitor Carpet Mill, William J.

Hogg's Oxford Carpet Mill, the Stinson Brothers' Columbia

Carpet Mill, and the carpet mills of Horner Brothers, and

Ivins, Dietz, and Magee (later of Hardwick and Magee).

The earliest carpet factories operated mainly through

"outwork" the owners providing yarns to workers who hand

loomed the goods in their homes. As these small

textile concerns grew, their owners built small factories

in East Kensington. 2

Associated

textile trades, such as dye works, yarn factories, woolen

and worsted mills, 3

cotton mills, and

even textile machinery factories were often located in

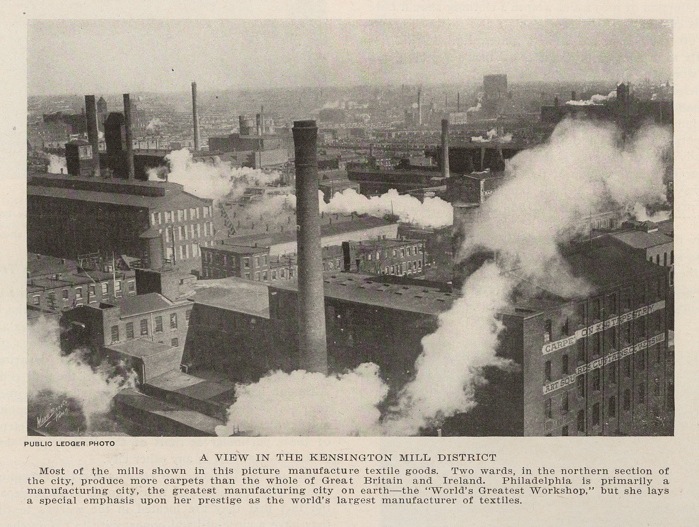

the same building or complex. After the 1860s, Kensington

was filled with two story brick rowhouses and steam

powered mills. In 1883, Lorin Blodget described the

northward expansion of the area as having had rapid and

successful development from vacant fields a few years

ago, to a densely built up city, all of which is recent,

and most of it within ten or twelve years. It is

wellbuilt, with broad and well paved streets, the mills

being especially well located, and many of those recently

erected being fine specimens of architecture

4

Development of the neighborhood first spread along the

early roads, such as Germantown and Frankford Avenues,

and the canals created out of Cohocksink and Aramingo

Creeks; however, new growth was spurred by the railroads.

The Reading Railroad ran east to west from the coal

wharves in Richmond, with various coal yards located

along the line. The painted signs and small buildings

associated with these yards, such as the Smith and Boyd

and the Magee, are still visible along Lehigh Avenue,

east of Front Street. The Philadelphia and Trenton line

traveled in the center of Trenton Avenue to a station on

the edge of Fishtown, where neighborhood protest

prevented continuation of the line into Philadelphia. The

North Pennsylvania Railroad ran up American Street, where

numerous factories, and lumber and coal yards took

advantage of a rail connection. 5

Small firms comprised most of the textile industry in

Kensington in the nineteenth century. For example, in

1850, most of the district's 126 textile firms each had

only one owner and few employees on site.

6

At the same time,

one third of the firms and workers in textiles in

Philadelphia were in Kensington. 7

Irish, English,

Scotch, and German immigrants, as well as native workers

and owners lived in the neighborhood, although not always

harmoniously, as the nativist riots of the 1840s

indicated. 8

These 4,000 plus

workers maintained a tradition of handlooms into the

1880s. Handloom operators were predominately male,

with female workers often working in the power mills

tending looms as well as performing other service

tasks. 9

In addition to textiles, Kensington had a high percentage

of tanneries and leather-working industries.

Blodget, in 1883, listed 21 Morocco and calf-kid

factories in the 16th and 17th Wards, with a product

valued at $4 million. 10

These

leather-working industries were in the district until the

latter 1950s. Both the Drueding Brothers, at Master and

5th Streets, and Dungan and Hood, at Susquehanna Avenue

and American Street, were listed in the 1957 Chamber of

Commerce business firms directory; their buildings still

stand. Burk Brothers, mainly connected with the Northern

Liberties area, had a glazed kid factory at Hancock and

Turner Streets in 1891. In addition to leather-working

establishments, there were slaughter houses and meat

distribution centers in the area. Both Swift and Armour

had meat-packing plants along American Street and there

were poultry markets as well.

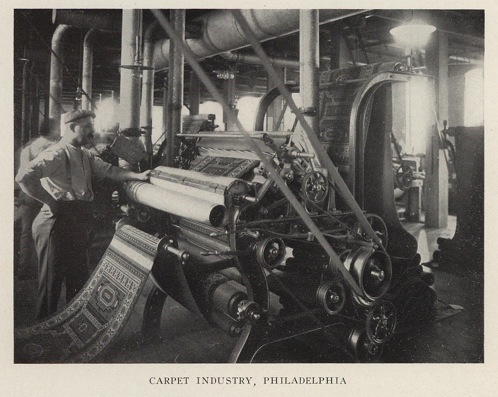

The diversity of

the textile trades in Kensington grew in volume

throughout the nineteenth century; however, the carpet

industry predominated. In 1882, 141 Kensington carpet

firms in the 19th and 31st Wards employed over 6,000

individuals and were valued at over $12 million.

11

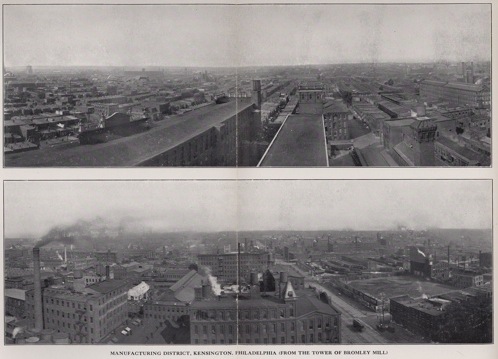

The largest of

these firms, John Bromley and Sons, covered more than a

city block at 201-263 East Lehigh Avenue before it was

destroyed by a fire in 1971. As with many Kensington

firms, the Bromley mills had several Kensington locations

before construction of the large power mill on Lehigh

Avenue.

"From the tower

of the Bromley Mill at Fourth & Lehigh Avenue there

are more textile mills within the range of vision than

can be found in any other city in the world. For miles in

every direction is seen the smoke of thousands of mills

and factories. To the northeast one continuous line of

factories extends through Frankford to Tacony, six miles

away. To the northwest through the smoke rising from the

Midvale works at Nicetown the mills of Germantown are

seen. To the west another line of mills stretched to the

Falls of Schuylkill and Manyunk. To the southwest are

Baldwin's and the foundries and mills of that section. To

the south are the hat and leather factories and the the

southeast are Cramp's shipyard and the numberless

industries clustered along the river Beyond all these are

the mills and factories of South and West bPhiladelphia,

some of them eight miles away."—Manufacturing in

Philadelphia, 1683-1912

Hosiery and knitting mills became more and more common in

the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By the

1920s, one third of Kensington's work force had shifted

from the carpet industry to employment in hosiery

mills. 12

These 11,000

workers produced all types of knit goods hosiery,

socks, fabrics, scarves, and sweaters. In 1928, 350 of

the city's 850 textile firms still operated in

Kensington, employing almost 35,000 workers. Of these

firms, 265 remained in 1940 after the Depression. During

World War II, some mills produced goods for the

government war effort, such as mosquito netting and

tarpaulins. The number of textile concerns shrunk to 75

in the late 1960s, and continues to shrink today. Most of

Kensington's mills stand abandoned and threatened by

deterioration and redevelopment. The creation of an

Enterprise Zone for redevelopment incentives on American

Street has meant the replacement of multistoried brick

building complexes with small, one story buildings. One

of the largest and most significant of Kensington's

factory complexes, the John B. Stetson Hat

Manufactory, no longer exists. Famous for their Western

hats, the Stetson Company made 3 million hats annually by

the 1920s. This complex, constructed between 1874 and

1930, included more than twenty buildings and over 30

acres of floor space. At its peak in the 1920s, more than

3,500 men and women worked at Stetson.

13

Stetson provided

a number of beneficial institutions for his employees,

including a hospital. All that remains of his domain is a

painted sign for the John B. Stetson Savings and Loan

Association on the corner of Germantown Avenue and

Montgomery Street. The plant closed in the 1960s.

14

1 Lorin Blodget,

Census

of Manufactures of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1883), p. 66.

2 Philip Scranton,

Proprietary

Capitalism: The Textile Manufacture at Philadelphia

1800-1885, (Philadelphia, 1983), p.

218.

3 According to the Oxford

English Dictionary, worsted originally referred to wool

made from "well-twisted" yarn, spun from long, staple

wool, combed to lay all the fibers parallel; it

eventually applied to fine and soft woolen yarn used

mainly for knitting and embroidery.

4 Blodget,

Census

of Manufactures of Philadelphia, p. 75-76.

5 T. Drayton, Plan of the

City of Philadelphia, (Philadelphia, 1830); and J. C.

Sidney, Map of the City of Philadelphia, (Philadelphia,

1849); and R. L. Barnes, Plan of the Built Portions of

the City of Philadelphia, (Philadelphia, 1855).

6 Scranton,

Proprietary

Capitalism, p. 189.

7 Scranton,

Proprietary

Capitalism, p. 182.

8 Scranton,

Proprietary

Capitalism, p. 187.

9 Scranton,

Proprietary

Capitalism, p. 193-194.

10 Blodget,

Census

of Manufactures of Philadelphia, p. 70, 73.

11 Blodget,

Census

of Manufactures of Philadelphia, p. 77.

12 Philip Scranton,

The

Philadelphia System of Textile Manufacture:

1884-1984 (Philadelphia, 1984), p. 16.

13 Federal Writers

Project, Works Progress Administration,

Philadelphia,

A Guide to the Nation's Birthplace

(Philadelphia

1937), p. 517.

14 Philip Scranton and

Walter Licht, Work

Sights, Industrial Philadelphia 1890-1950

(Philadelphia,

1986), p. 169.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to

Harold E. Spaulding, who provided in-depth research on

the history and present-day sites of Lower North

Philadelphia, which contributed to the chapter overview

as well as the survey of buildings.

Resources:

Kensington

bibliography