Northwest corner Estaugh & J Streets.

Luithlen Dye Corporation, c.1880-2003

Ward Elicker Casting, 2004-

J Street between Estaugh & Tioga, Philadelphia PA 19134

© Carmen A. Weber, Irving

Kosmin, and Muriel Kirkpatrick, Workshop of the World (Oliver

Evans Press, 1990).

In the 1880s Ludwig B.

Luithlen established a dye works in rented space in

Kensington. Sometime around 1895, he moved to a one story

brick dye house on the corner of J and East Estaugh

Streets in the Harrowgate section. The firm served the

large numbers of textile industries located in Kensington

throughout the twentieth century; despite the decline in

these industries, it still continues to operate.

Although the Luithlen name is still associated with the

dye works, it has operated under several families in the

twentieth century. Under Emil Viet, the dye works

employed twnty-nine males and an office work force of

four people in 1916. 1

Viet ran the

Luithlen Dye Works until 1919. At that date, the Wiegand

family acquired the company. The firm employed between

sixty and forty-two people in the 1940s.

2

Incorporating in 1948, Louis Wiegand, Jr. is now the

third generation to operate the company. The one story

brick building, with a monitor along its roof line, holds

forty-four dye kettles. Narrow fabrics, yarns, carpet,

bindings, tapes, and zippers are dyed in these kettles,

which are heated by steam supplied by two 500 horsepower,

oil fired boilers. The two story brick building on the

corner of Tioga and J Streets holds storage space as well

as the finishing department and drying room. The drying

operation utilizes steam to operate a range, ten dryers,

and twelve yarn winders. 3

1 Department of Labor

and Industry, Pennsylvania, 1916, p. 1286.

2 Chamber of Commerce

and Board of Trade, Philadelphia, p. 39.

3 Interview with Louis

Weigand, Jr., President, (October 27, 1988).

East facade along

J Street.

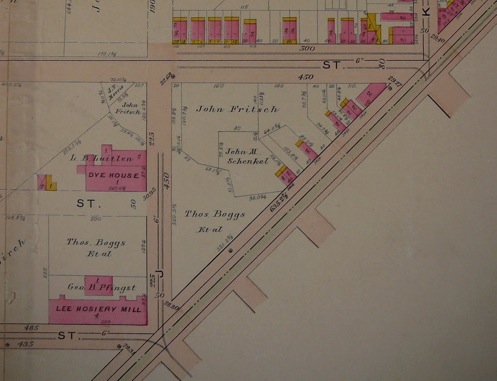

Undated map

(<1900) showing "L.B. Luithlen Dye House" on the

northwest corner of Estaugh & J Streets. Tioga Street

is at the top, Kensington Avenue is on the diagonal.

Collection of Ward Elicker Casting.

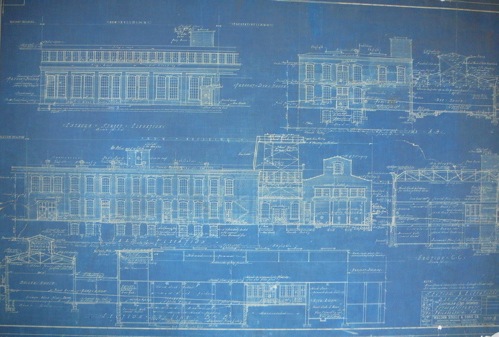

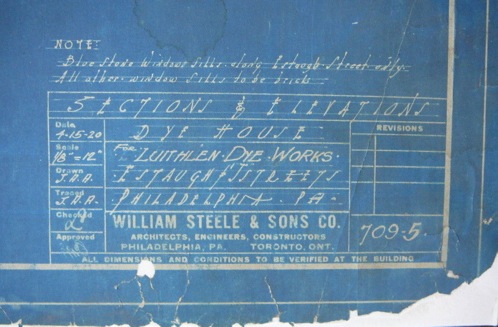

Sections &

Elevations of the Dye House for Luithlen Dye Works drawn

by William Steele & Sons, April 15, 1920. Collection

of Ward Elicker Casting.

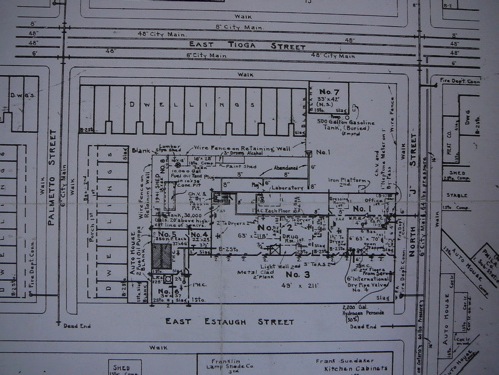

Plan of Luithlen

Dye Works by Factory Insurance Association, 1973.

Collection of Ward Elicker Casting.

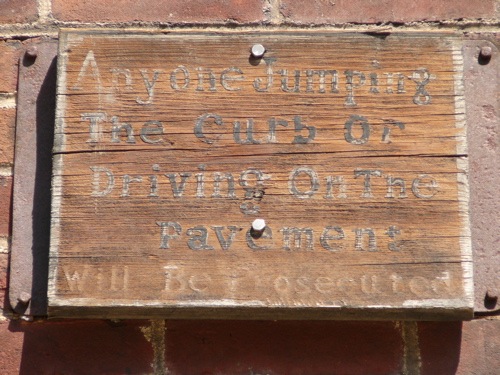

"Anyone Jumping

The Curb Or Driving On The Pavement Will Be Prosecuted"

— sign along Estaugh Street.

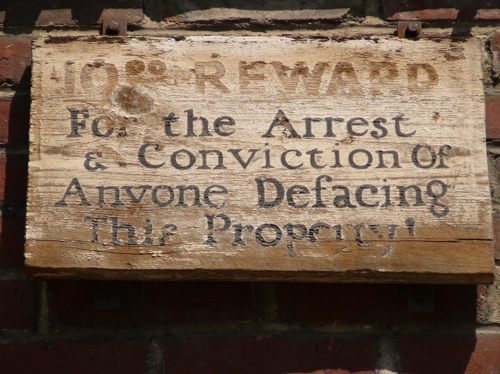

"$10.00 REWARD For the

Arrest & Conviction Of Anyone Defacing This

Property!" — sign along Estaugh Street.

Update May

2007 (by

Torben Jenk):

Luithlen Dye was sold to

Wayne Mills in 2003, which then moved the dyeing

operations to Manyunk.

The

site was sold and is now occupied by Ward Elicker

Casting. For the SIA June 2007 conference,

Jeb Wood, CEO and

Metalsmith of Ward Elicker Casting, offered a tour of the

foundry and explained the entire process of translating

an artist’s work (often in clay) into a finished

sculpture in bronze or iron. Known as “lost wax

casting” the process involves making the mould,

making the wax casting, chasing the wax, spruing, casting

the ceramic mould, burn out, casting, break out,

sandblasting, assembly, chasing, glass beading, polish,

patina, waxing, mounting and inspection. Elicker Casting

serves emerging artists (some rent space in the building)

and renowned contemporary sculptors like Tom Otterness,

Julian Schnable, George Segal and Kiki

Smith.

Most of the

dyeing equipment has been removed to accommodate the new

sculpture foundry, Ward Elicker Casting.

Ceramic shell

molds are being burned out to remove the wax. Molten

bronze will be poured into these shells.

Some Civil War

monuments were cast in "white bronze" (cast zinc).

Examples like this were cast in large numbers, only the

face being personalized. Now deteriorating, Ward Elicker

Casting can take new molds and cast these monuments again

in long-lived real bronze.

A brief

history of sculpture and casting in Philadelphia.

(Torben Jenk

2007)

More than just making machines, Philadelphia has a

centuries old tradition of supporting the arts and

artists. In 1795, the first public monument in

Philadelphia was installed over the entrance to the

Library Company of Philadelphia, a marble figure of Ben

Franklin. The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, founded

in 1805, is the nation’s oldest art museum and

school of fine art. In 1872, concerned citizens who

believed that art could play a role in a growing city

formed the Fairmount Park Art Association to purchase,

commission and maintain art works from the world’s

leading sculptors including Daniel Chester French, Paul

Manship, Frederick Remington, Jacques Lipschitz, Henry

Moore and all three generations of the Calder family:

Alexander Milne, Alexander Stirling and Alexander

“Sandy.” Thousands of artworks, large and

small, abstract and commemorative, are displayed

throughout the city.

Philadelphia’s most

famous sculpture, “William Penn” stands atop

City Hall. Sculpted by Alexander Milne Calder, it is

thirty six feet tall and weighs 53,000 pounds -- the

largest single piece of sculpture on any building in the

world. The Tacony Iron Works started casting it in

1890 and the bronze sculpture was set in place in 1894.

For

the past twenty five years graduates of the Pennsylvania

Academy of the Arts, the University of the Arts, Temple

University and other art programs have sought experience

and training in the comprehensive Johnson Atelier in

Hamilton, NJ, founded by J. Seward Johnson who believed

“There is no art more dependent on it’s

technical aspects than sculpture. An ignorance of

technique limits a sculptor’s creativity, wastes

hours of work in bringing a cast to likeness of the

original, and renders the artist captive of the

foundry’s trade secrecy and commercialism. Until

the Industrial Revolution, however, the opposite was

true. The home of the foundry was the sculptor’s

studio where the results of poor practices and errors in

judgement were immediately visited upon the artist, for

it was the artist who created and cast their own work.

This system led to quality and efficiency.”

Johnson wanted to

“restore the link and the interplay which used to

exist between the sculptor and the founding of their

work” with the goal “to educate and train

more artisans to be available to aid the sculptor in

completing their task, to develop methods for making

these processes less costly and more responsive to the

sculptor’s needs, and finally, to play a small part

in whatever forces must come together to bring more

sculpture into the 20th century lifestyle.”

When the Johnson

Atelier was reorganized a few years ago some of their

highly skilled staff artists and artisans built their own

small foundries in Philadelphia.