Fairmount Water Works, 1812-1815, 1819-1822, 1851, 1859-1862, 1868-1872

Aquarium Drive, Philadelphia PA

© Jane Mork Gibson,

Workshop of the

World (Oliver Evans Press, 1990).

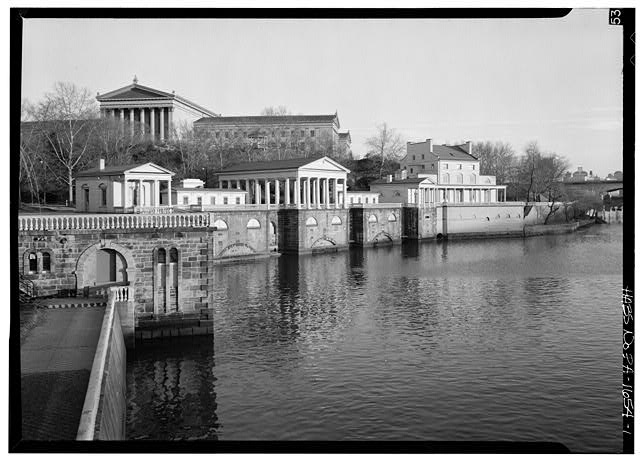

The Fairmount Water Works is

one of the most striking examples of industrial

archeology in Philadelphia. The complex of buildings

located on the east bank of the Schuylkill River north of

the Spring Garden Bridge, represents an innovative

approach that was undertaken by the city in 1812 to

provide a municipal water supply following the

inadequacies of the earlier Centre Square system that

began operations in 1801. The buildings were constructed

or remodeled in five stages that mirror the changes in

the technology involved. 1

Charged with providing a sufficient supply of potable

water for the city, the Joint Committee on Supplying the

City with Water, known as the Watering Committee, had

been formed in 1798 and was made up of members of the

Select and Common Councils of Philadelphia. Frederick

Graff had assisted Benjamin Henry Latrobe at the Centre

Square Works and was appointed Superintendent in 1805. He

continued in this position at the Fairmount Water Works,

and is responsible for the design of most of the

buildings and the technology, utilizing portions of the

earlier system. Upon Graff's death in 1846, his son,

Frederic Graff, Jr., was appointed Superintendent,

serving until 1856, and again from 1867 to 1872.

The first stage in the development of Fairmount Water

Works employed steam engines to power the pumps, in the

same manner as in the Centre Square system, except that

two engines were housed in one building so that if one

was inoperable, the other could take on the "duty," and

the greatly feared danger of lack of water during a fire

could be avoided. The Engine House at Fairmount was

therefore designed to house two steam engines—a low

pressure Bolton & Watts style engine built by Samuel

Richards, or Foxall-Richards, at the Eagle Works in

Philadelphia and the Weymouth Forge in South Jersey, and

a high pressure Columbian noncondensing steam engine

built by Oliver Evans at the Mars Works in Philadelphia.

The low pressure engine had a steam cylinder 43-5/8 in.

diameter and a six foot stroke; the lever beam was 23 ft.

9 in. long between centers and was cast in two leaves;

the pump was double acting, 20 inches diameter, and with

a 6 foot stroke. At first it was operated at 2.5 psi, but

this was increased to 4.0 psi after the flue of the

chimney was enlarged. It took seven cords of oak wood to

raise 2,116,882 U.S. gallons to the reservoir.

2

The high pressure engine had a cylinder 20 inches in

diameter and differing records indicate both a 48 in. and

a 60 in stroke; the pump was vertical and double acting,

20 in. diameter. The engine was 100 horse power, and

pressure was at times carried at 220 psi, but this was

not considered safe. There were two explosions and three

deaths due to the primitive state of the boilers and also

possibly due to the inattentiveness of the attendants. It

took ten cords of oak wood in 20 hours to raise 100

gallons 98 feet at each stroke, at 24-3/4 strokes per

minute; the capacity was confirmed to be 3,556,401

gallons in 24 hours.

On the exterior, the Engine House resembled a federal

mansion rather than an industrial facility, and the

interior did not have the normal floor levels but was a

great open space so far as possible to accommodate the

flywheels and other parts of the two steam engines.

Construction was started in 1812 and the system was in

operation in 1815. Water was drawn from the Schuylkill

River and pumped 96 ft. to the reservoir located at the

top of the hill, where the Philadelphia Museum of Art is

presently located. The high expense of operation,

estimated at $30,858 annually for either engine, and the

need for a greater supply of water led the city to

consider alternative systems in 1819. The Committee

decided to dam the Schuylkill at Fairmount and construct

a water-power system, employing breast wheels.

The city purchased the water power rights at the Falls of

the Schuylkill from Josiah White and Joseph Gillingham in

1819 and proceeded to construct a dam across the

Schuylkill at Fairmount in conjunction with the

Schuylkill Navigation Company. The dam would create a

pond from which water for pumping and for power could be

drawn. The six-foot fall was increased by the tidal

conditions below the dam, but high tide was a hinderance

causing backwater twice a day when the wheels had to

stop. Ariel Cooley was engaged to build the dam,to

consist of a 1204 foot long crib dam from the west bank -

allowing for the canal locks there—to an earthen

mound dam built to extend 270 feet out into the river

from the east bank. 3

The millrace and

space for the mill house on the east bank were blasted

out of solid rock.

HAER

Frederick Graff designed the mill house to enclose eight

breast wheels, fifteen feet wide and sixteen or eighteen

feet in diameter. The lower section of the building was

divided into twelve apartments for eight individual

forebays and four pump chambers containing two pumps

each. Thomas Oakes was the millwright who advised on the

form of the water wheel and the mill machinery. The first

three wheels were of wood, constructed by Drury Bromley

and Thomas Oakes. The remaining five were of cast iron

with wooden buckets, and were made by Rush &

Muhlenberg (sons-in-law of Oliver Evans, deceased), Levi

Morris, and Merrick & Towne. The wheels were

installed gradually from 1822 to 1843, and the first

three were replaced in 1846 by I.P. Morris with the wood

work and breastings done by Edward Heston. The speed of

the wheels varied from 11 to 14 rpm, and capacity of the

pumps varied from 91.08 to 121.4 gallons per revolution.

The pumps were situated almost horizontally and had a 16

in. diameter, with the strokes varying from 4-1/2 to 6

feet. Additional reservoirs were added on Morris Hill

(Faire Mount) above the water works until there were four

reservoirs with a capacity of 22,031,976 gallons in 1836.

The exterior of the mill house took on neoclassical lines

with the construction of two small tempiettos at each end

as a Watering Committee Building and a Caretaker's House.

The Engine House was remodeled in 1835 after removal of

the steam engines and became a public "saloon" where

refreshments were served, and the surrounding grounds

were landscaped to become a public garden. The porch

added on the river side in 1835 gave the Engine House a

neoclassical aspect to harmonize with that of the mill

house. The Fairmount Gardens thus became the forerunner

of what was to become Fairmount Park.

The third stage in the development of Fairmount Water

Works was the introduction of a small experimental Jonval

turbine in 1851, which is still "in situ," although some

parts are missing. Room for the turbine and gear train

was created between the Engine House and the Mill House,

with the pump room located under the terrace of the

Engine House. The turbine runner was 7 feet in diameter

with 30 buckets and operated at 44 rpm. The gearing

reduced the speed to 12 rpm to power a reciprocating

force pump similar to those in use at Fairmount.

The installation was under the direction of Emile

Geyelin, who had the franchise for Jonval turbines in the

United States. The new turbine had a draft tube and

was not affected by backwater, raising 1,685,016 gallons

in 24 hours. A standpipe was erected in 1852 to

accommodate the new reservoir at Corinthian Avenue, which

was a quarter of a mile away and was at a higher

elevation than the Fairmount Reservoir.

The fourth stage was the construction of the New Mill

House alongside the Mound Dam (1859-1862). This was done

to add three larger Jonval turbines to the facility and

provide a greater supply of water for the growing city.

The Act of Consolidation in 1854 had incorporated all of

the outlying districts as part of the city. John

Birkenbine was the Chief Engineer in charge of the new

addition to Fairmount. The machinery installed was

state-of-the-art and the additional pumpage required the

construction of a distribution arch leading to the

standpipe.

A continuing need to increase the water supply led to the

fifth stage which consisted of a complete remodeling of

the Old Mill House to accommodate three more large Jonval

turbines. These were installed between 1868 and 1872

under the direction of Frederic Graff, Jr. The work

included extending the river wall in places, and

rearranging the structures on the deck so that they

appear as they are today. The classical open pavilion

added in 1872 by Frederic Graff, Jr. reflected an earlier

drawing made by his father c.1920.

Fairmount Water Works in its heyday of the 1830s and

1840s was the most well-known scene of Philadelphia, and

the increasing improvement in the surrounding grounds

made it a favorite recreation spot for Philadelphians and

visitors alike. The opportunity to observe the water

wheels, pumps, and turbines made it of special interest.

And, of course, the water flowing over the dam—if

the water was high enough—was also worth watching.

Pollution of the river became a concern as early as the

1840s but little was done about it except for penalties

which were assessed and generally ignored. It was not

until the 1890s that scientific evidence was sufficient

to compel the city to build filtration plants. When

these were completed in 1909, Fairmount Water Works was

taken "off line" except for a few customers, and the

facility was decommissioned in 1911 and turned over to

the Mayor for use as a Public Aquarium.

HAER

The industrial use of the structures had ended. The

machinery—except for the 1851 Jonval turbine,

gearing and pump—was removed by March 1912. The

reservoirs were drained and construction of the

Philadelphia Museum of Art on the site was begun in 1919.

The standpipe and distribution arch were demolished in

the 1920s. In 1975 the American Society of Civil

Engineers declared Fairmount Water Works a National

Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, in 1976 it was

designated a National Historic Landmark by the U.S.

Secretary of the Interior, and in 1977 the American

Society of Mechanical Engineers made the water works a

National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark.

Through a concerted effort of public and private agencies

since 1974, Fairmount Water Works is being restored as a

recreational area, with a strong emphasis on its

utilitarian past. The existing industrial archeology

includes not only the 1851 Jonval turbine, gearing and

pump in situ, but also excavated artifacts including

portions of the 1872 Jonval turbine, which had been

removed to make place for the Aquarium, and portions of

the 1851 turbine vanes and runner removed c.1930 when a

sewer line was routed through the tailrace of the

turbine.

The complex of buildings and the physical features

present an opportunity to understand the past activities

of the history of the site. An Interpretive Center

focusing on the history of Fairmount Water Works and the

value of a city water supply is planned as part of the

restoration effort. This will enable visitors to learn

what was there and how it worked.

1 For a more complete

rendering of the history than is possible here, see Jane

Mork Gibson, "The

Fairmount Waterworks," Bulletin of the Philadelphia

Museum of Art, Vol. 84, Nos. 360 and 361, Summer 1988;

also, Jane Mork Gibson, Historical Report, and Susan

Stein, Architectural Report, Historic American

Engineering Record Collection, Fairmount Water Works,

HAER PA-51, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

2 Measurement was by ale

gallon (282 cu. in.) until 1854 when the standard, or

wine, gallon was adopted (231 cu. in.).

3 See Workshop

of the World "Fairmount Dam" for more details.

Update May

2007 (by

Jane Mork Gibson):

When the Fairmount Water Works was decommissioned in

April of 1911, the buildings and one pumping unit were

turned over to the Mayor for use as an aquarium, which

opened in November of that year. Due to a change in the

city administration, the buildings were placed in the

charge of the Fairmount Park Commission the following

spring. All of the pumping equipment was removed except

for the small Jonval turbine in the basement of the

former Engine House, which was used to provide the water

needed for the aquarium. Although the First World War

slowed down conversion, by the 1920s the Philadelphia

Aquarium was state of the art and was one of the four

largest aquariums in the world. The Engine House was

converted for office use and the main floor served as a

Lecture Hall, where attendees could watch fish in many

small aquarium tanks that had been used in the 1893

Chicago Fair and the 1905 St. Louis Fair. New discoveries

in making large strong sheets of glass for the aquarium

tanks made it possible for visitors to watch fish

swimming at eye level, a novelty at the time. The Old

Mill House contained freshwater fish, and the New Mill

House seawater fish. At one time seals from Atlantic City

spent the winter in the forebay. After a series of

mishaps, and consistent underfunding, the Aquarium closed

its doors in December of 1962.

In the 1980s, as a result of the public interest in

Fairmount Water Works and the desire to preserve the

facility, the Old Mill House, where water wheels once

turned, was stripped of aquarium construction in the

interior, and the structure was restored as a large open

space. Water storage tanks in the basement of the Engine

House were removed. The New Mill House, which had been

converted into an Olympic swimming pool, was only

structurally repaired as necessary.

Following a careful restoration of the buildings

comprising Fairmount Water Works, in 2003 the Fairmount

Water Works Interpretive Center opened in the Old Mill

House and on the lower level of the Engine House.

Reflecting the restoration effort, the city changed the

name of the street from Aquarium Drive to Water Works

Drive. The Interpretive Center provides an opportunity to

tell the two-hundred-year history of water supply in

Philadelphia, and in its exhibits focus on how

people’s actions on the land can make a difference

to their water. The displays and interactive exhibits

cover the many concerns about preserving the quality of

the city’s water. Educational programs, which

include lab participation, inform on existing conditions,

and on what can be done to improve them. As the Delaware

River Basin’s Watershed Education Center, classes

are held for school children and lectures are open to the

general public. A short movie with digital animation

tells the story of Fairmount Water Works, illustrates how

the water once flowed through the building and how the

machinery had worked. Beside the building itself, the

only artifacts remaining are the Jonval turbine and

gearing, together with the double-acting pump installed

in 1851. The Center is open Tuesday to Saturday from 10

a.m. to 5 p.m, and on Sundays from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m.

Admission is free.

The Water Works Restaurant and Lounge, located in the

Engine House and the Caretaker’s House, opened in

July of 2006 under the aegis of Michael Karloutsos.

Previously small cafés and restaurants had operated at

the Engine House on a seasonal basis with an appreciative

clientele, but no permanent plans were made. In 1981, the

existing café closed after a fire in the building.

Subsequent efforts for a restaurant were delayed by

another fire in 2002. After these many false starts,

Philadelphia has responded enthusiastically to the

establishment of the Water Works Restaurant, contributing

to the preservation and appreciation of this site.

At the 14th Annual Preservation Award Ceremony on May 2,

2007, the Preservation Alliance of Philadelphia presented

a Grand Jury Award for the South Garden and Cliffside

Restoration. The citation is reproduced here:

Originally

designed by Frederick Graff in 1829 as a romantic

landscape, by the 1990s the South Garden, adjacent to the

Water Works, suffered from vandalism and lack of

maintenance. The Fairmount Park Commission and the Fund

for the Water Works commissioned a comprehensive Historic

Landscape Report, which, in part, determined the

“target" date for the restoration should be 1875,

by which time all the essential elements were in place.

While the setting for the restoration is a designed

landscape, the restoration’s main focus was on the

architectural and built features. The Marble

Fountain—which hadn’t operated for more than

115 years—was dismantled and reconstructed after

underground water service was reinstated. The 1848

Gothic-inspired Graff Memorial underwent extensive stone

and metal restoration and conservation, and the return of

the bust of Frederick Graff.

The elaborate cast-iron railings—largely missing by

the 1990s—along with the Cliffside Path which

connects to the Art Museum were recreated, and the path

itself was stabilized and paved. Other historic features

were also introduced, including reproduction light

fixtures, benches, and ornamental railings. Now thousands

of visitors can once again experience the South Garden as

originally conceived.

See

also:

Fairmount Water Works Interpretive

Center

Historic American Enginering Record -

Fairmount Waterworks, Aquarium

Drive

Historic American Engineering Record -

Fairmount Waterworks, East bank of Schuylkill

River

The

Fairmount Waterworks, by Jane Mork Gibson

(Philadelphia Museum of Art, Bulletin Vol. 84,

#360-361, Summer 1998). 48 pages, well illustrated

with color and black & white plates, technical

drawings and maps, 8-1/2" x 11". Published on the

occasion of the exhibition "The

Fairmount Waterworks, 1812-1911"

(July

23-September 25, 1998), celebrating the restoration

of the waterworks.

The

Fairmount Waterworks, by Jane Mork Gibson

(Philadelphia Museum of Art, Bulletin Vol. 84,

#360-361, Summer 1998). 48 pages, well illustrated

with color and black & white plates, technical

drawings and maps, 8-1/2" x 11". Published on the

occasion of the exhibition "The

Fairmount Waterworks, 1812-1911"

(July

23-September 25, 1998), celebrating the restoration

of the waterworks.