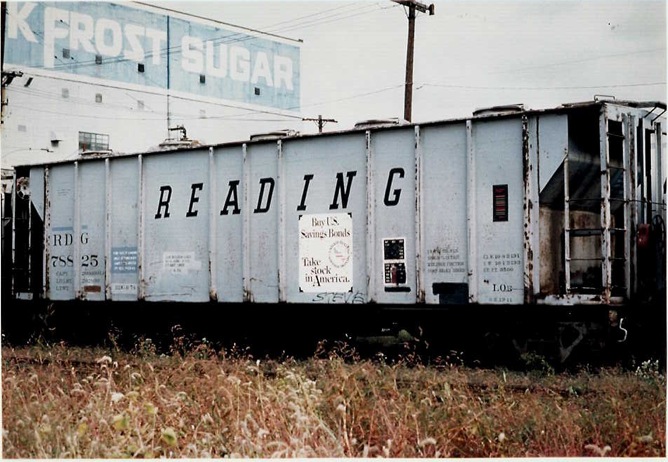

Reading Railroad covered hopper car #78825 was specifically assigned to Jack Frost to carry refined sugar to customers. The blue patch near the left end of the car just to the right of the "25" reads "For sugar loading only. When empty return to RDG Co Pt Rch, Pier 43".

Jack Frost Sugar Refinery, c.1901-1940

1001-1071 Penn Street, Philadelphia PA 19125

© Stuart Paul Dixon,

Workshop of the

World (Oliver Evans Press, 1990).

In 1881, Fishtown's first

sugar refinery, owned by the Pennsylvania Sugar Refining

Company, began operating in the area bounded by the

Delaware River to the south, Laurel Street to the west,

Penn Street to the north, and Shackamaxon Street to the

east. The complex also includes one building on the east

side of Shackamaxon Street connected to the rest of the

complex by an above-ground conveyor system. The National

Sugar Refining Company, better known as Jack Frost,

acquired Penn Sugar in 1947. Active sugar refining at the

complex halted in 1984 after National Sugar sold the

property.

Composed of approximately eighteen buildings on the

Fishtown waterfront, the Jack Frost complex today stands

as a silent reminder of Fishtown's past industrial

vitality. Among these eighteen buildings are a

by-products building, pan house, melter house, char

house, bagging facility, boiler house, pump house,

storage sheds, an office building, and a shipping and

receiving building. The complex was described in 1937 as

rising "in a strangely shaped geometrical brick mass,

from which protrude at fantastic angles a variety of

tanks and metal pipes." 1

This description

depicts the complex's appearance to this

day.

Beginning at the northwest corner of the complex, a

six-story reinforced-concrete building, eight bays in

width faces Penn Street. Built in 1924, this structure

functioned as the by-products building. East of it is a

six-story, three-bay building; according to an 1950

Sanborn insurance map, it contained a laboratory with

filler tanks. A seven-story, 10-bay pan house with a

raised brick cornice and a shallowly-sloped center gable,

stands to the east of the preceding two buildings. A date

stone set in the pediment of the gable gives 1901 as the

year of construction. Remodeled in 1927, this structure

contained pulverizers on the first and second floors and

dry ovens on the third floor; the dry ovens were used in

preparing the raw sugar for melting. East of the 1901 pan

house, a three-story boiler house stands with eleven

exhaust stacks protruding above its roof. The boiler

house was described by the 1950 Sanborn as containing

engines and dynamos on the first floor, and economizers

on the second. A three-story warehouse and office

building stands to the east of the boiler house; behind

it is a twelve-story char house. A one story

shipping and receiving building, erected in 1940 stands

to the east of the office building across Shackamaxon

Street.

Buildings to the rear of these structures consist of a

seven-story melter house, a six-story fire tower, a

nine-story refinery, and a seven-story char house; the

char house was constructed in 1901. Another three-story

boiler house lies to the rear along, with a nine-story,

five-bay by thirteen-bay-deep pump house with coal

bunkers. A five-story steel-frame warehouse built in 1915

sits on a pier in the Delaware River, along with a

three-story storage house, a three-story facility for the

bagging and storage of raw sugar, and a three-story wharf

house. A four-story rum and gin storage house rises on

another pier into the Delaware River.

When the Pennsylvania Sugar Refining Company began

operations at this site in early 1881, it occupied five

buildings rebuilt from an earlier soap and oil works.

From molasses and syrup, Penn Sugar manufactured soft and

brown sugar, employing approximately 40 men in the

process. Two boilers were used to refine the sugar, while

a 100 h.p. engine drove 24 centrifugal machines. The

original brick and frame buildings were demolished as

Penn Sugar expanded and rebuilt the facilities to their

near-present state in the early twentieth century. Penn

Sugar appears as six brick buildings in a 1895 atlas. A

1910 atlas shows three large brick buildings and a frame

wharf. In 1916, Penn Sugar employed over 300 men and

women, and had an office staff of 73 people.

In the 1930s, the refinery imported dark brown, raw sugar

in 325-pound bags from Caribbean and Pacific basin

islands. 2

Unloaded at the

refinery's docks on the Delaware, the sugar was dumped

into hoppers and conveyed to the melter house where the

sugar crystals were saturated with syrup in minglers.

Centrifugals, similar to clothes dryers, washed the now

fluid sugar free of impurities and molasses. The fluid

sugar was then converted into a thick syrup in the

melters, "a maze of piping and tanks." After filtering

through metal cloth covered with silica, the syrup was

pumped "to the char house, a 12-story building filled

with an array of pumps, piping, batteries of filters 10

feet in diameter by 25 feet deep, and oil-burning kilns

for revivifying the char."

The filtered liquid then proceeded to the pan house,

where "large tanks built of heavy copper plates and

fitted with steam coils, a condenser, and a vacuum pump"

lowered the temperature of the syrup, compelling the

liquid to form crystals. The size of the crystals varied

from fine "caster sugar" to one-quarter-inch rock candy.

"Centrifugals (bronze baskets 40 inches in diameter, with

finely perforated screen perimeters) spin toplike at a

speed of 1,000 revolutions per minute, ejecting the syrup

while the crystals remain on the screen to be washed. The

wet sugar is delivered to the revolving dryers for drying

and separation into various sizes." Automatic weighing

and packing machines filled the sugar into bags and

cartons that had capacities ranging from 2 to 100 pounds.

For some customers the sugar was packed in wooden barrels

that contained 350 pounds.

Cubes and tablets were made in cylindrical presses, while

powdered sugar was made in pulverizers from standard

sugar. The last product of the refining process, called

black strap molasses, was sent to the by-products

building. "Here it is used for alcohol production, being

mixed with yeast which breaks up the glucose into alcohol

and carbonic acid gas." The gas had its alcohol content

boiled off in a continuous still and was then packed for

sale as an antifreeze, a flavoring, and a solvent.

1 Federal Writers

Project, Works Progress Administration,

Philadelphia,

A Guide to the Nation's

Birthplace,

(Harrisburg, 1937), p. 532.

2 The description of the

following sugar production process was taken from

the WPA

Guide to Philadelphia (1937), pp. 532-33.

Demolition (1997).

Update May

2007 (by

Torben Jenk):

On June 29, 1997, the

ten-story Jack Frost Sugary Refinery withstood multiple

attempts to destroy it with explosives. On Nov 2, 1997,

with 700 lbs of explosive set in 4,000 charges, the

remaining building was successfully imploded through

"controlled demolition." After a detailed structural

analysis, a minimum amount of explosives is strategically

placed in holes drilled in critical support columns or

strapped to support beams. These are detonated in an

exquisitely timed sequence lasting from milliseconds to a

full nine seconds. Weight and gravity do the

rest. The goal is to implode things down, usually

collapsing a structure inward within its footprint but

sometimes the building is laid down in a predetermined

direction to avoid damage to adjacent structures.

In December 2006, this site was one of two selected for a

casino along the Delaware River in Philadelphia. The

investors are promoting it as the "Sugar House Casino"

and propose a $550 million casino and entertainment

project with up to 5,000 slot machines operating 24 hours

a day. The legislation permitting casinos was introduced

by state politicians seeking new revenues for

Pennsylvania, supported by wealthy local investors.

Because the enabling legislation limited the voice of

neighboring residents and even the Philadelphia Zoning

Board, lawsuits and petitions have been filed and are

winding their way through the courts.

See

also:

History of the Pennsylvania Sugar

Company—Jack Frost, Ken Milano (presentation

May 24, 2006).