- © Philadelphia in the World War, 1914-1919 (Philadelphia War History Committee, 1922), pp. 428-431. Information on Ford Motor Company by permission of William Bradford Williams.

The steel helmet, or "Doughboy's Iron Lid" of World War fame, was one of the many articles of equipment designed for the American Expeditionary Forces produced by the Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Company [and the Ford Motor Company], Philadelphia, Pa.

In August, 1917, work was begun and the first shipment made within a period of four weeks, during which time the proper grade of sheet steel was purchased, and dies designed and built to press the sheets into the proper shape to fit over the head.

The material used was a high grade manganese steel, which was received at the plant in square sheets 16 inches by 16 inches. Every sheet was immediately subjected to a breakage test by impressing in one corner a small ball-shaped punch. If the metal broke under the punch the sheet was rejected, but if the sheet showed a sound cup-shaped depression, it was passed on to a double action press, in which the punch drew the flat sheet into the die and formed the bowl or helmet shape.

The next step involved the trimming die, which cut the rim to proper size and shape. A metal edging was then put around the rim to cover the raw edge of steel left by the previous trimming operation, and electric welded at the joint. The edging was then clinched securely to the helmet under a press. Holes were then pierced in the helmet to receive the rivets for holding the lining as well as the loops on both sides to receive the chin straps. The loops were attached by riveting in a small punch press. After buffing the welded joint of the edging to make a smooth finish, the manufacturer's identification number was stenciled on, and every helmet submitted to the inspector for rigid examination.

The United States Government maintained a corps of inspectors at the works who would pick out a certain number of helmets, approximately one in every fifty, for a ballistic test. This was accomplished by attaching the helmet to one end of a 10-foot pipe, 6 inches in diameter, in such a position as to receive a blow on its convex surface. At the other end of the pipe a 45 caliber army revolver was mounted. The bullets would make an indentation in the helmet of from 1/4 inch to 3/4 inch deep without breaking the steel, and would often rebound the entire length of the 10-foot pipe to the revolver mounting.

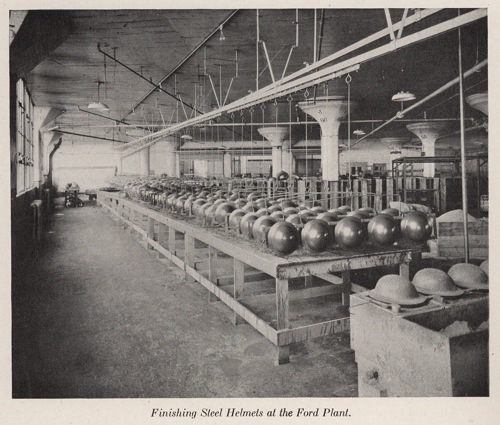

After passing inspection, the helmets were loaded on trucks, and delivered to the Ford Motor Car Company, Broad Street and Lehigh Avenue, Philadelphia, where they were painted, had the linings attached, and were packed for shipment.

The Budd Company shipped a total of 1,160,829 helmets, and when the war operations ceased had orders on their books for approximately a million and a quarter more which was subsequently canceled.

FORD MOTOR COMPANY

From the triangular-shaped, ten-story Ford plant, at the corner of Broad Street and Lehigh Avenue, there was shipped every steel helmet sent abroad to the American forces. Every doughboy of the millions that helped to hurl back the German horde has reason to thank the Philadelphia branch of the Ford Motor Company for whatever portion was allotted to him of the 2,719,600 steel hats that deflected many a death-dealing bullet and saved many an American life.

In the experimental field also, the Quaker City plant did its share of the work. When the War Department endeavored to produce a further safeguard for our soldiers abroad, namely, the eye-guards, 35,622 were manufactured at Broad Street and Lehigh Avenue. A body armor that recalled bygone martial days, 10,000 suits of it were also assembled, enameled and shipped from the local plant of the Ford Company.

All of the foregoing does not take into account some 384, Ford machine gun trucks that were thoroughly repaired, overhauled and shipped abroad to the American fighting forces.

NO PROFIT TO ACCRUE

In considering the work done by the Philadelphia branch on its various helmet and other contracts, the distinctive fact must be borne in mind that it was all accomplished under Henry Fords specific instructions that no profit was to accrue from any of the work performed.

Before the Philadelphia Ford branch was approached by the Government officials as to its willingness to undertake helmet contracts, the lowest bid tendered by concerns was thirty-one cents per helmet.

The contract for the first million helmets was drawn with the understanding that the maximum price would be thirty-one cents per helmet, but that if the production costs proved less, the difference would be refunded to the Government.

Completion of the 1,000,000 helmets showed the cost to be $.1036 per helmet, a saving of $.2064 per helmet, or a total saving of over $197,000 on 955,516 helmets delivered on the first contract.

During peace times and previous to America's entry into the war, each day at the Philadelphia Ford branch saw the building of tops, bodies and the painting and upholstering operations for the assembling and shipment of 150 complete Ford automobiles.

Among the Ford equipment at the plant was a highly developed special department where fenders and body stock received treatment that transformed them from the raw steel units, such as individual fenders and completed bodies, to the enameled and highly polished finished products that enter into completed automobiles. In doing this work, among other equipment, a battery of the largest and most carefully constructed ovens in the East figured as most important.

PLANT INVESTIGATION

September, 1917, after an investigation of the enameling equipment in this section of the country, by several representatives of the Ordnance Department, had produced no definite results, the Philadelphia branch of the Ford Motor Company was visited and inspected by these same Government officials.

A quick survey of the facilities there promptly convinced them that the plant's enameling equipment and general efficiency methods employed made it by far the most likely firm that could entirely fulfill their requirements.

They accordingly requested the local Ford Manager, Louis C. Block, to accept a contract for the enameling and sanding, the fitting and riveting of the headgear inside of the steel helmets.

They stated their needs called for 7,200 helmets per day, a production, in their opinion, that would necessitate two working shifts a day. As a matter of history, as soon as production was started, the Ford staff exceeded this production by a big margin and by working only one shift per day.

As the armed forces of the country were increasing in excess of 7,200 per day, a production of 15,000 helmets per day was soon called for. This production was reached, notwithstanding that all such helmet work was entirely new to this country. New methods and equipments had to be developed.

Under the original specifications, the helmets were first painted, then sprinkled with sand and baked, after which they were finally repainted and baked again. The reason for this utilizing sand was to prevent the possibility of sheen on the helmets while worn by soldiers, thereby reducing visibility.

After numerous experiments, it was suggested that sawdust be substituted for the sand, as this substance was not only much more effective in producing the desired result, but when scraped from the helmet did not expose points of shining metal. Subsequently, specifications were changed accordingly.

The steel helmets were arranged in racks of ten, and during the entire operation of painting, sawdusting by a specially devised contrivance, repainting and baking,

this series of ten units was maintained.

The assembling of the headgear inside the helmet was the next step in their production. Owing to the lining requirements, the question of packing the units for overseas shipment developed into the greatest obstacle to rapid production.

It was found that nine minutes were required to pack each box of twenty-five helmets. Experimentation again brought startling results. A compressed-air packing machine was devised and this same work was now performed in about thirty seconds.

General Pershing was continuously calling for more and more helmets. Officers of the Ordnance Department consequently approached the Ford plant, asking if it were possible to still further increase production.

When advised that production had now reached the stage where it was only a question of receiving the necessary material to reach almost any figure necessary, they promptly stated they would see to it that the materials were supplied.

A steady stream of material permitted an increase to 40,000 helmets per day. At this stage the local plant, if called upon, could have reached a maximum production of 75,000 helmets per day.

It was just about this time that the armistice was declared. The Ford Company still had contracts for the completion of almost 2,000,000 more helmets. Notwithstanding this, they immediately informed the Ordnance Department that they were willing to release the government from the contracts, which offer the Ordnance Department quickly accepted.

While engaged on the helmet contracts, the War Department, in December, 1917, collected from all the National Guard regiments, mustered into the regular army, 384 Ford machine gun trucks. All of these trucks were shipped to the local plant of the Ford Company and were put into first-class condition as speedily as received and shipped abroad to the waiting fighting forces.

EYE-GUARDS AND BODY ARMOR

About this time the Engineering Bureau of the trench warfare section of the Ordnance Department was engaged in experimental work on eye-guards and body armor. At the request of the official in charge of this work, a contract was awarded the Ford plant to paint, assemble and pack for shipment over 35,000 eye-guards, 5,000 suits of front body armor and 5,000 suits of back body armor.

Being work of purely an experimental nature, changes of specifications were numerous, causing unforeseen delays. Nevertheless, the job was completed to the entire satisfaction of the Engineering Bureau.

To summarize, the following was the contribution of the Philadelphia Ford plant towards the winning of the world conflict:

2,749,600 steel helmets,

35,622 eye-guards,

5,000 suits of front body armor,

5,000 suits of back body armor,

384 machine gun trucks repaired.