As evidence, this page is archived as it stood through January 7, 2008.

—Compiled by Torben Jenk

with contributions from Denis Cooke, Ken Milano, Rich Remer, Hal

Schirmer, Dr. Robert Selig & others.

Can further archeology at the site of the proposed

SugarHouse Casino help reveal the location of British

Redoubt [fort] No.1, and/or provide physical evidence of

the line of redoubts which forced Washington to retreat

to Valley Forge for the harsh winter of 1777-1778? Many

remember Christmas 1776, when Washington led his troops

across the Delaware to defeat the Hessians in Trenton,

NJ, but one year later, in 1777, just a few months after

losses in Brandywine and Germantown:

"On

Christmas day Washington

prepared a plan for a surprise attack on the

redoubts north of

Philadelphia. ... The main force approached the line

of [British]

redoubts

and exchanged a few cannon shot without inflicting any

damage. After probing the line of redoubts, Washington

considered the defenses too strong and retired to Valley

Forge." —John W. Jackson, "With the

British Army in Philadelphia 1777-1778" (Presidio, 1979),

pp. 169-170

The

Sugar House Archeology Report (Oct.

2007) by A.D.

Marble & Company does not cite any maps prior to

John Hills (1797)—yet scores of maps, drawings,

surveys, manuscripts and journals survive, providing a

wealth of clues for the Engineers, archeologists,

historians and citizens. Local historians read that

report in early December and immediately noticed the

omission of any Revolutionary War information, or

anything else from the documented history of this area

dating to even before William Penn's arrival in 1682.

On December 12, 2007, an email was sent to the

archeologists raising this concern about Redoubt No. 1

and included a surviving map from 1777, drawn by John

Montresor, Chief Engineer of the British Army in

Philadelphia. The archeologists responded that same

day stating "cannot comment."

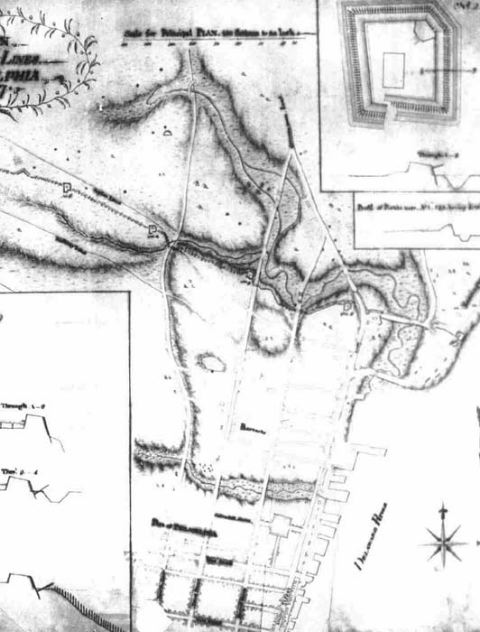

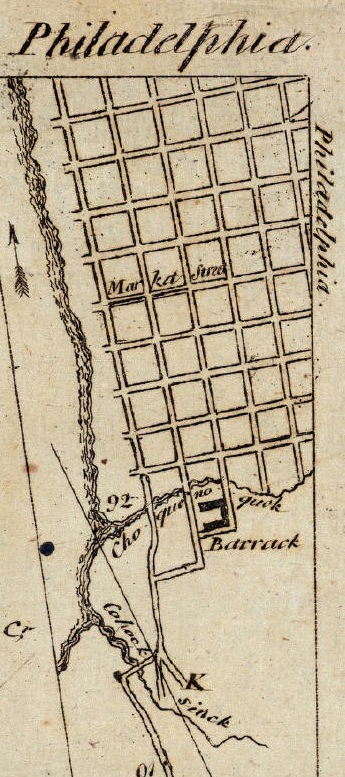

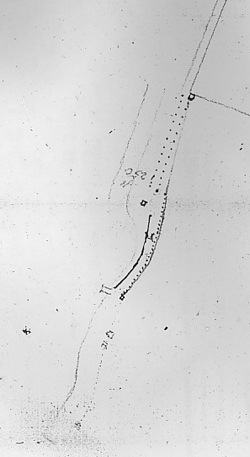

—Detail

showing Redoubt "No. 1" clearly sits on or adjacent to

the SugarHouse property, near the edge of the Delaware

River on a line with Laurel Street (shown as the bridge

over the marsh. Collection: Library of Congress.

The

subsequent SugarHouse Archeology Report (Dec. 28,

2007) states on

page 4

"... it came to A.D. Marble & Company's attention

that a Revolutionary War period fort was potentially

located within the subject property..."

Yet that

report cites NO other documentary evidence about the fort

or the Revolutionary War era—NONE. This webpage

gathers over fifty historical resources revealed by local

historians in just the past few weeks. More are being

added every few days.

Page 5 of the Dec. 28 report states

"We believe no other significant remains from the

fort exist. If any remains could possibly exist, it would

only be the filled in portion of the depression that

likely surrounded the fort. It is our contention that any

remains of any kind would be difficult to interpret

without the existence of the overall resource. No further

action is recommended within the area of the former

Fort."

Archeologists aren't needed if the "overall

resource"—i.e. the entire fort—survived.

Proof exists that Redoubt No. 1 survived for fifty years

after the Revolutionary War, until just before 1830.

Built on a hill, the soils and artifacts were surely

scattered nearby to fill to the bulkhead line or other

depressions.

"The

British redoubts remained til lately—one on the

Delaware bank in a line with the stone-bridge

street—then no houses were near it; now it is all

built up, and streets are run where none were

seen."

—John

F. Watson, "Annals of Philadelphia" (1830), p.

418

As proof that even older items survive even today on the

SugarHouse site, page 3 of the Dec. 28 report

states:

"A small area measuring 50 x 30 feet within the

central portion of Historic Area H-1 was identified as

containing Native American artifacts. This area was

extensively investigated... yielded primarily artifacts

identified as primary and secondary flakes of jasper,

quartz and argillite, probably created during the

manufacture or maintenance of stone tools. Of secondary

frequency was a collection of fire-cracked rock that did

not form any distribution patterns in any of the four

excavation units that would suggest the presence of a

hearth. A broad-bladed, stemmed point was also recovered

within this area."

Finding

Reboubt No. 1 would reveal 18th century British military

engineering, so admired by Major General Charles Lee of

the Continental Army in America, who had bitterly

complained of the incompetence of American engineers,

remarking that "we had

not an officer who knew the difference between a

chevaux-de-frise and a cabbage garden."

—"Up from the depths of history, a remnant

of the Revolution is pulled from the Delaware" Phila.

Inquirer, Nov. 15, 2007.

Skeptics say "nothing can be found" but in November 2007,

a "cheval-de-frise" was found "in excellent condition"

after more than two centuries in the Delaware River; "it

was probably placed in the river in 1775, at a time when

the Pennsylvania Council of Safety, under the direction

of Benjamin Franklin, was overseeing the colony's

defense." This example survived off Fort Mifflin, despite

the best efforts of the Corps of Engineers to remove them

all in 1946. Documents show that "chevaux-de-frize" and

other items, large and small, were used by the

thousand-plus British and Loyalist soldiers to defend the

redoubts and abatis just north of Philadelphia. Stories

of other archeological finds from disturbed sites in

Philadelphia are on the Philadelphia Archaeological

Forum.

Redoubt No. 1

was built in 1777, just east of the Cohocksink Creek, to

protect the causeway and bridge linking Front Street from

Philadelphia to the main 18th century route between

Philadelphia and New York, known then as the "King's

Highway" or the "Road to Frankfort and N. York"

[Frankford Avenue]. Redoubt No. 1 served as the base and

barracks of the Queen's Rangers under the command of

Lieut. Col. John G. Simcoe, from which they protected

both the crossing of the Cohocksink and that

transportation route to bring food from the Loyalist

farmers in Bucks County to the 60,000 occupants of

Philadelphia.

20th century historians unfamiliar with the massive

changes to the landscape around the long-buried

Cohocksink Creek have mistaken and misplaced its

location, adding to the confusion. In 1701 the Cohocksink

was a navigable creek which powered William Penn's

Governor's Mill but by 1898

it was buried as a sewer. The edge of the Delaware

River has also changed through industrialization

during the 19th century. Local historians have spent

over a decade searching through surveys, deeds, maps,

journals and extant structures to reveal the

long-buried history of this area known as "Point

Pleasant", which prior to the Revolution was also home

to the famed Bachelor's Hall (burned 1776) and

Master's Distillery & Tide Mill, and by 1809

included the Point Pleasant Iron and Brass Foundry

started by Charles Parke to cast bells.

To clarify the inconsistencies of some early maps and

views (especially those produced in England after the

Revolution), relevant quotes are added from various

historic sources including. John F. Watson interviewed

folks who lived through the Revolution for his "Annals of

Philadelphia" and "In

early times, the 'North End' was the common name given to

the Northern Liberties, when having its only road out

Front street. In the present notice it will include the

region of Cohocksinc creek over to Kensington, and

westward over the former Campington. The object is to

bring back to the mind's eye 'its face of nature, ere

banished and estranged' by improvement."

Other captions associated with these various maps,

images, photos and text reveal the contradictions and

complexities—yet hopefully clarify the best of

current research. By sharing these historic resources, we

honor the founding motto of the U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers—"Essayons"

or

"we will try."

After a brief introduction to the area around the

SugarHouse site showing surviving landmarks, scores of

maps, drawings, photos, and words describe the history of

the Cohocksink and Point Pleasant. Where possible, links

are provided to the original sources. A through list of

resources is provided, with links where possible to the

original sources. Further historic material information

is being scanned and prepared. Contributions of relevant

information are welcomed and will be added.

-----

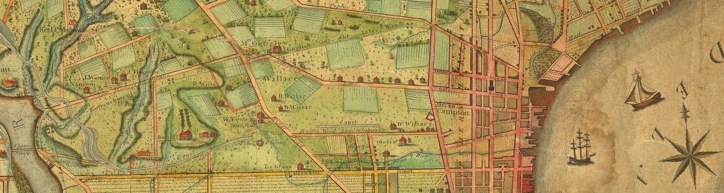

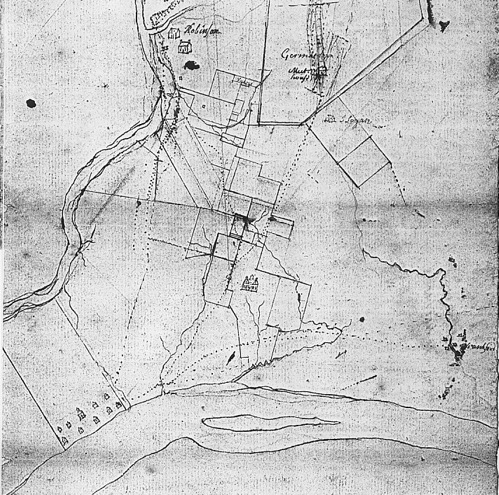

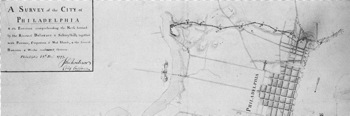

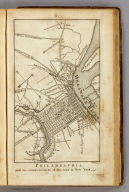

—Detail

from "A survey of the city of

Philadelphia and its environs shewing the several works

constructed by His Majesty's troops, under the command of

Sir William Howe, since their possession of that city

26th. September 1777, comprehending likewise the attacks

against Fort Mifflin on Mud Island, and until it's

reduction, 16th November 1777. Surveyed & drawn by P.

Nicole. Anotated: John Montresor, chief engineer."

Library of Congress

Detail showing

the ten redoubts across the north of Philadelphia, from

"No. 10" along the Schulkyll River atop Fairmount (now

the Art Museum) to "No. 1" along the Delaware River near

the foot of Frankford Road (possibly on the site of the

proposed Sugar House Casino). Front Street is between

Redoubts No. 1 & 2, splitting left to the "Road to

Germantown" (now Germantown Avenue) and right to cross

the marshes of the Cohocksink Creek by causeway and

bridge, connecting to the "Road to Frankfort and to N.

York" (now Frankford Avenue), and through "Kinsington" is

the "Point-No-Point Road" (now Richmond Street) towards

the mouth of the Frankford Creek, about five miles up the

Delaware River.

The "Fall or Wissahiccon Road" (at left) is now Ridge

Avenue. The C-shaped structure east of the "A" in

Philadelphia is the British Barracks, or "Campington",

which stood between Second and Third Streets, near Green

(just above Spring Garden Street). Pegg's Run is the

lower creek which ran along today's Willow Street, just

north of Callowhill Street.

The

northern defense line started by [Chief Engineer]

Montresor in late September [1777] had received very

little attention from the army engineers until after the

batteries on Carpenters' and Province islands were

completed. Work had, however, continued on the redoubts

with civilian laborers being supervised by army officers

and an occasional engineer. ... While Howe was still in

Germantown, it was not considered necessary to man the

fortifications under construction. The five miles between

Philadelphia and Germantown were under constant patrol,

and few American soldiers were to be found in the area.

Rarely, an American patrol came down the Frankford Road,

but always withdrew without challenging the makeshift

British defenses. When the British moved their main army

from Germantown into the City on 19 October [1777],

immediate steps were taken to defend the unfinished

redoubts. Various British and Hessian battalions and

regiments were assigned positions in the rear of the

redoubts. With the

rails and straw transported from Germantown, huts were

constructed to serve as temporary quarters. As materials

were in short supply, every fence within reach was carted

away, and most farmers in the Neck [South Philadelphia]

and near the lines lost their straw. Howe proposed to

quarter the troops in the huts until winter made it

unlikely that Washington would attack and until he could

ascertain where the American army would establish its

winter encampment. Although Howe continued to abhor the

thought of a winter campaign, he was not as certain of

Washington's plans, especially after the surprise attack

on Trenton the previous Christmas. Regardless, it was

evident that the British soldiers could not live in their

huts beyond mid-December—even though Washington's

Continentals would live in similar huts in Valley

Forge. —Jackson, John W.,

With the British Army in Philadelphia 1777-1778

(Presidio, 1979), pp. 95-96

Wonderful descriptions of the activities around Fort No.

1 in 1777 survive, see the:

"First hand accounts of the

activities surrounding the British Redoubts built just

north of Philadelphia,

1777-1778",

"Excerpts from the Journal of Lieut. Col.

John G. Simcoe and the Queen's Rangers in

Revolutionary Kensington" ,

Simcoe's Military Journal

,

The Journals of Capt. John

Montresor,

or this excerpt from "The Manuscript of Colonel Jarvis,

An American's Experience in the British Army"

Fighting

at Germantown under the Colors of the

King

In this day's hard fought action, the Queen's Rangers'

loss in killed and wounded were seventy-five out of two

hundred fifty rank and file which composed our strength

in the morning. Why the army did not the next day pursue

the enemy, and bring them to action, I must leave to

wiser heads than mine, to give a reason, but so it was.

We remained encamped the whole of the next day, and gave

the enemy an opportunity to rally his forces, get

re-inforcements and take tip a position to attack us,

which they did, at Germantown, where our Army had

encamped, sending our sick and wounded into Philadelphia.

At this battle the enemy were again defeated, and left us

in possession of the field. On the morning of this

action, I was under a course of physic, and was ordered

to remain in camp, and had not the honor of sharing in

the victory of this day's battle; I was so reduced from

fatigue that I was returned, unfit for duty, and was

ordered to the Hospital, and the next day took my

quarters at the Hospital in Philadelphia. I was not so

ill but that I could walk about, and the Doctors allowed

me to take a walk about the City every day. Whether they

had any orders from my officers on that behalf I know

not, but so it was when others had not the same

indulgence. I remained in the Hospital until I thought I

was able to undergo the fatigue of duty and join my

Regiment.

A few days after joining the Regiment, made an excurtion

into the Jerseys, as far as Hattenfield, but

it was

ordered that I should remain at the quarters of the

Regiment, which was at Kingsonton.

The next

day Captain Dunlap returned to the quarters ordering

every man that was able to march to join the Regiment,

and myself among the rest. It was near dark when we got

to the Regiment. I was most dreadfully fatigued, and lay

down to rest. I had hardly time to take my refreshment

before the Regiment was ordered under arms, where we

remained for several hours in a storm of hail and snow,

and at last ordered to retrace our steps towards

Philadelphia. I had

marched but a few miles before a pain attacked my limbs,

to that degree, that I could with difficulty walk, and

soon fell in the rear of the Regiment, expecting every

minute to fall into the hands of the enemy. I had the

good luck to get up with the Regiment, who had encamped

at a plantation on the banks of the Delaware. More dead

than alive, the ground covered with snow, I scrambled to

the barn, got into a large mow of straw, covered myself

up with straw, and fell asleep and did not wake until

daylight in the morning. On awaking, I heard Major Simcoe

(who had a short time before, and while I was in the

Hospital) succeeded Major Wymes in the command of the

Regiment, and some of the officers in another part of the

barn, but hid from my sight. They soon left the barn, and

left standing on a beam within my reach a bottle partly

filled with good madeira. I soon demolished the contents

and set the bottle up as before, left the barn also, and

joined my Company. In the course of the day the Americans

attacked us, and we had a smart brush with them, had a

Sergeant (McPherson of the Grenadiers) and several men

wounded. In the evening we crossed over to Kensington and

took up our old quarters.

—The Journal of American History, 1907, p. 450

-----

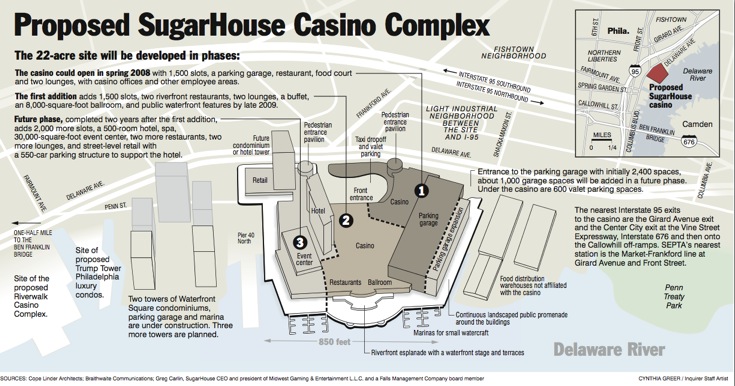

—Drawing from

Philadelphia Inquirer

The ancient path of the Cohocksink Creek is shown under

the "a" in "Casino", between "food" and "court" and then

winds left under much of the text, then empties (not

drawn) into the Delaware River at the "Site of proposed

Trump Tower" where Penn Street and Delaware Avenue

meet. Note how the

22-acre site of the SugarHouse site spreads from

Shackamaxon Street to below Frankford Avenue.

-----

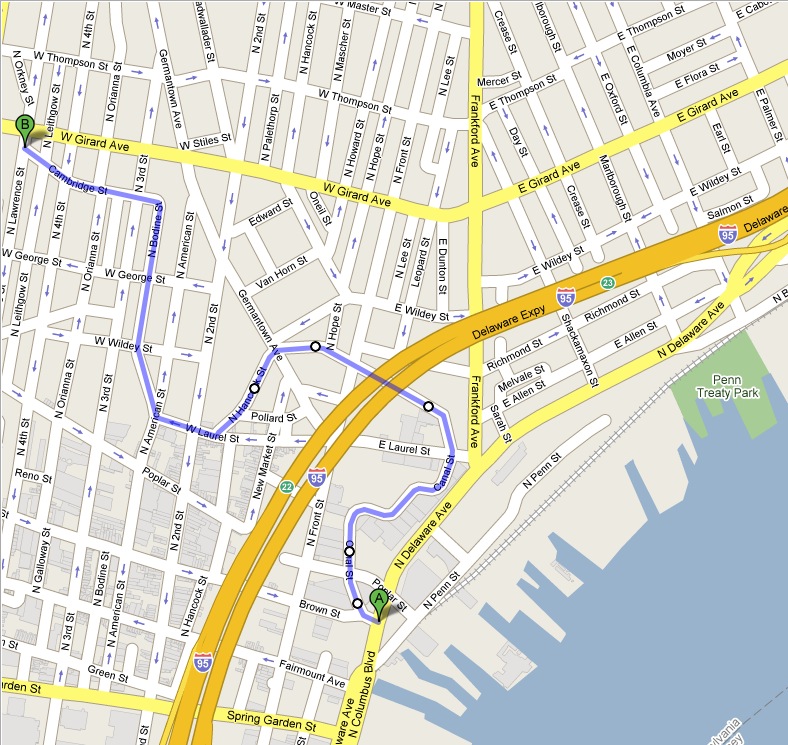

—Map

created on Google Map.

Despite being

turned into a canal and then a sewer, the lower parts of

the Cohocksink are clearly evident under parts of the

streets we know today as Canal, Allen, Hancock, Laurel,

Bodine, Cambridge and Orkney; and in the oddly-shaped

buildings which straddle the creek. Point A is near Pier

35, Point B is where the creek crosses under Girard

Avenue. The Governor's Mill stood

northeast of the ninety degree bend from Cambridge to

Bodine Street. The area below the Frankford Road but

east of the Cohocksink Creek to the Delaware River was

known in Colonial times as "Point Pleasant."

-----

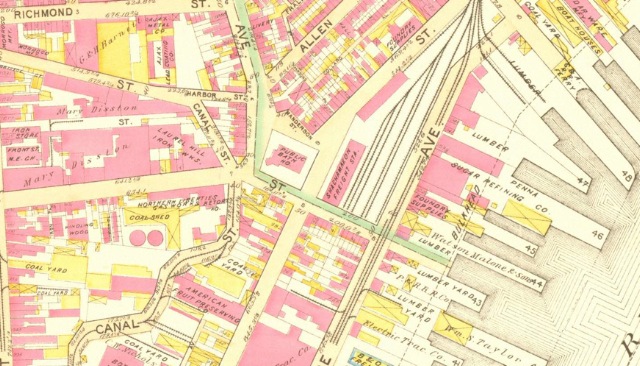

—Detail

from "Atlas of the City of Philadelphia, 1895"

George W. & Walter S. Bromley, Plate

13.

The "Sugar

Refining Co." (see Pier 46) stood on the riverside of

Delaware Avenue, between and below Shackamaxon Street

(above Pier 48) and Frankford Ave (terminating at the

"PUBLIC BATH HO[USE]." Note also the winding "Canal

St."

-----

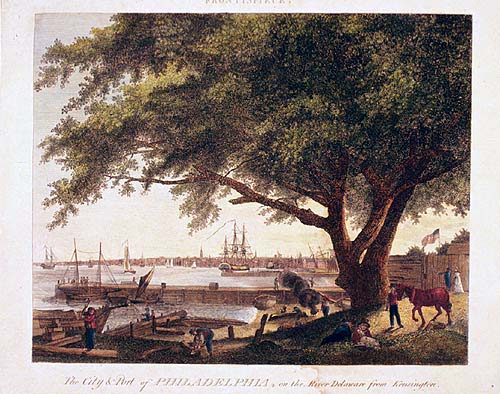

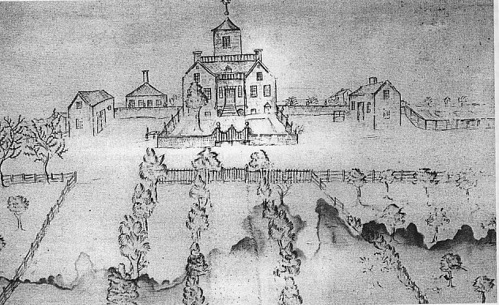

Robertson

draws the mouth of the Cohocksink in 1777.

—"View

of Philadelphia." [Lieutenant General Royal Engineers]

Archibald Robertson, November 28, 1777. Drawing in sepia.

38 x 54.3 cm. Source: Spencer Collection, New York Public

Library

Martin P.

Snyder in "City of Independence—Views of

Philadelphia Before 1800" (Praeger, New York, 1975), pp.

115-6, reproduces this drawing and states: "Archibald

Robertson was one of the British engineer officers

participating in the occupation of the city. Two weeks

after the battle of Fort Mifflin had ended with American

withdrawal, he crossed to the New Jersey shore and

rendered in sepia wash a beautiful view of

Philadelphia—seemingly securely British—from

the distance. Its size permitted considerable detail and

its quality is apparent."

This seems incorrect. Robertson's title—"View of

Philadelphia"—is accurate since the City's northern

boundary was then at Vine Street. Robertson's original

drawings and diary survive in the New York Public Library

but were "being conserved" and therefore unavailable for

inspection when I tried to find other substantiating

notes a few years ago. In 1930, the NYPL published the

drawings and diaries in "Archibald Robertson,

Lieutenant-General Royal Engineers: His Diaries and

Sketches in America, 1762-1780 (Harry M. Lydenberg,

Editor).

A crucial clue—ignored by Snyder and

others—is the causeway from the bluffs of Northern

Liberties to Kensington, linking Front Street from

Philadelphia to the beginning of the Frankford Road.

Instead, it seems Robertson was along the northern bank

of the Cohocksink Creek—one of the three characters

drawn in the foreground—looking south to

Philadelphia including the tall steeple of Christ Church

(2nd & Market Streets) and the lower steeple of St.

Peter's (3rd & Pine Streets), southwest to the houses

of Northern Liberties (the bluff being near today's

Second and Poplar Streets), and southeast to "Point

Pleasant," or the beginning of Kensington.The buildings

at the left are likely part of Thomas Masters Distillery

and/or Tide Mill. Thomas Masters had yet another mill,

the Governor's Mill, farther

upstream but also powered by the Cohocksink, where the

liquor store now stands at the southwest corner of

Germantown & Girard Avenues]. The frame structure

in the middle of the water might have been used for

fishing.

In 1739,

Mrs. Mary Smith with her horse were both drowned "near

the long bridge in the Northern Liberties." "Twas

supposed it occured by her horse attempting to drink at

that place where water is very deep." At the same

causeway was quicksand, in which a horse and chair and

man all sunk!—John F.

Watson, "Annals of Philadelphia" (1830), pp.

415-420.

-----

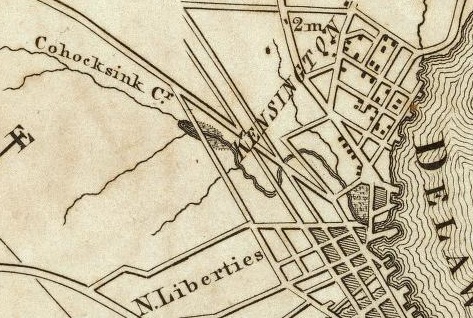

Detail,

mouth of the Cohocksink Creek between Redoubts No. 1

& 3 (1777). Front Street then terminated east of

No. 2 with the "Road to Germantown" heading

northwest. A causeway and bridge crossed east over

the Cohocksink marshes towards No. 1, from which,

heading north is the "Road to Frankfort and to N.

York" (now Frankford Avenue), while heading

east-north-east through "Kinsington" is the

"Point-No-Point Road" (now Richmond Street) towards

the mouth of the Frankford Creek, about five miles

up the Delaware River.

While the

British army occupied Philadelphia, in the year 1777 and

'78, they damned in all the Cohocksinc meadows, so as to

lay them all under water from the river, and thus

produced to themselves a water barrier of defence in

connection with their line of redoubts across the north

end of the city. Their only

road and gate of egress and ingress northward, was at the

head of Front street where it parts to Germantown, and by

Kensington to Frankford. —John

F. Watson, "Annals of Philadelphia"

-----

November

22 [1777] was an eventful day in Philadelphia, starting

with a phenomenon of nature, followed by an act that was

the "Shame the British Nation," and ending with the

joyful news that ships were finally coming through the

river obstructions. At about 7:00 A.M. "a pretty shock of

an earthquake was felt earthquake, probably because they

were distracted by the wanton destruction of many estates

north of the redoubts, between the city and Germantown.

The exact number of homes which were needlessly burned is

not known. Deborah Logan said she saw seventeen fires

from the roof of her mother's house on Chestnut Street;

other eyewitness accounts give varying numbers, but all

deplored the action. Robert Morton's observations best

epitomize the reaction of Loyalists and Americans alike.

“The reason they assign for this destruction of

their friends' property is on acco. [account] of the

Americans firing from these houses and harassing their

Picquets. The generality of mankind being governed by

their interests, it is reasonable to conclude that men

whose property is thus wantonly destroyed under a

pretence of depriving their enemy of a means of annoying

y’m [sic] on their march, will soon be converted

and become their professed enemies. But what is most

astonishing is their burning the furniture in some of

those houses that belonged to friends of government, when

it was in their power to burn them at their leisure. Here

is an instance that Gen'l Washington's Army cannot be

accused of There is not one instance to be produced where

they have wantonly destroyed and burned their friends

property.”

Joseph Reed wrote Thomas Wharton: "The enemy have made at

destruction of the little villas in the neighborhood of

their lines. The bare walls are left; the doors, windows,

roofs and floors are all gone to make huts. Not the least

trace of a fence or fruit tree is to be

seen.”—Jackson, John W.,

With the British Army in Philadelphia 1777-1778

(Presidio, 1979), pp. 104-105

-----

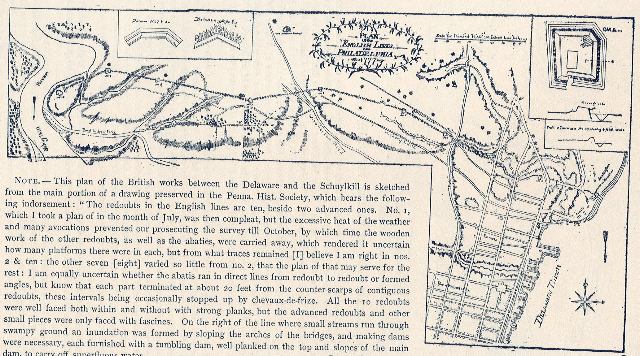

Plan of the English

Lines, Philadelphia 1777.

—Scan

of Plan of the English Lines Philadelphia

1777 . Original

source "Narrative and Critical History of

America," Justin Winsor (Editor), (Houghton, Mifflin

& Co., Boston, 1887), Vol VI, p. 440.

[Note, this

eight volume work was expanded to a sixteen volume

work by 1889 and it has been reprinted subsequently.]

The caption reads:

NOTE: This

plan of the British works between the Delaware and

Schuylkill is sketched from the main portion of a drawing

preserved in the Penna. Hist. Society, which bears the

following indorsement: 'The redoubts in the English lines

are ten, besides two advanced ones. No. 1, which I took a

plan of in the month of July, was then compleat, but the

excessive heat of the weather and many avocations

prevented our prosecuting the survey till October, by

which time the wooden work of the other redoubts, as well

as the abaties, were carried away, which rendered it

uncertain how many platforms there were in each, but from

what traces remained [I] believe I am right in nos. 2

& ten; the other seven [eight] varied so little from

no. 2, that the plan of that may serve for the rest; I am

equally uncertain whether the abatis ran in direct lines

from the redoubt to redoubt or formed angles, but know

that each part terminated at about 20 feet from the

counter-scarps of contiguous redoubts, these intervals

being occasionally stopped by chevaux-de-frize. All the

10 redoubts were well faced both within and without with

strong planks, but the advanced redoubts and other small

pieces were only faced with fascines. On the right of the

line where small streams run through swampy ground an

inundation was formed by sloping the arches of the

bridges, and making dams were necessary, each furnished

with a tumbling dam, well planked on the top and slopes

of the main dam to carry off superfluous water.

LEWIS

NICOLA.

Enlarged plans

and cross-sections of redoubts nos, 1, 2, and 10 are

given in the margin, as well as the western advanced

redoubt, and other small works, including the "Barriers

across Kensington and Germantown roads with a

cremaillered work between them cut out of the bank

between the roads." The stars near the lines denote the

places of "houses destroyed by the English." Cf.

description in Penna. Mag. of Histo., iv. 181

-----

Plan of British Defenses, north side of

Philadelphia, 1778 shows close ups of the riverfront

fort and construction details.

-----

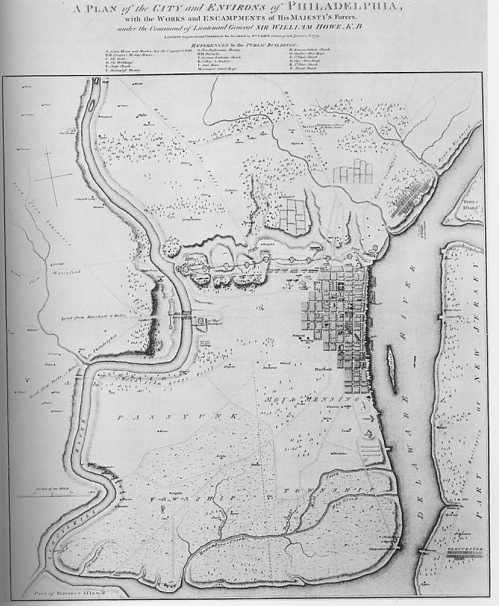

Faden

redraws Montresor, confuses Pegg's Run & Cohocksink

Creek.

—"A

Plan of the City and Environs of Philadelphia with the

Works and Encampment of His Majesty's Forces...", William

Faden's engraving (1779) and "Atlas of Battles of the

American Revolution" (London, 1793).

William Faden,

engraving this map in London in 1779, confuses Pegg's Run

with the Cohocksink Creek—a mistake clearly visible

when comparing it to Montresor's original below (drawn in

Philadelphia in 1777, now in the collection of the

British Museum), which shows Pegg's Run just north of

Philadelphia with the defenses along the Cohocksink

Creek. —Both

maps copied from Martin P.

Snyder, "City of Independence—Views of Philadelphia

Before 1800" (Praeger, New York, 1975), pp.

116-119.

—Detail, "A Survey

of the City of Philadelphia & it's Environs ... &

the several Batteries & Works constructed thereon,"

John Montresor Chief Engineer, 31-7/8" x 27-3/8",

collection of the British Museum.

-----

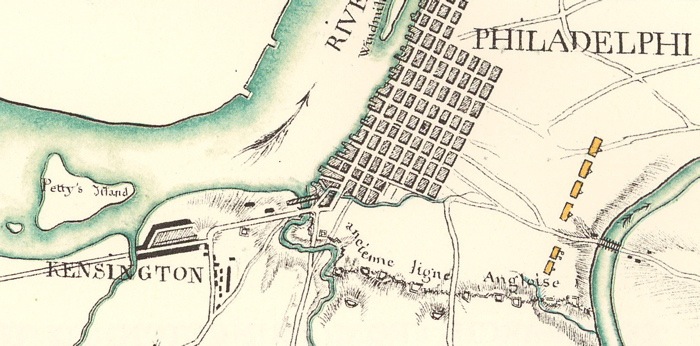

Rochambeau's

march, 1781-1782

—Detail from

"Read's Lion tavern à Philadelphie" [March from Red Lion

Tavern to Philadelphia], MS, 22 x 33 cm, Princeton

University Library, Bethier Papers, No. 16-4, reproduced

in Howard C. Rice Jr., & Anne S. K. Brown

(translators and editors), "The American Campaigns of

Rochambeau's Army, 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783", (Princeton

University Press, 1972).

3-4 September 1781. "The road bears right a bit but

nevertheless comes closer to the river. On either side of

the road you find woods, county houses, and ruins that

are monuments to the wrath of the English. Half a mile

from the city you see remains of General Howe's lines.

Soon you cross one of the works that the English had

built for the defense of the town. The road turns left,

you cross a brook called Cohocksink Creek, pass through

the suburb of Kensington, and reach

Philadelphia."—"The American Campaigns

of Rochambeau's Army," Vol II, p. 75.

See the "ancienne ligne Anglaise" on the map, described

above as "remains of General Howe's lines." Kensington is

shown at the mouth of the next creek, the Aramingo Creek.

As part of their 625-mile march, over 5,000 troops under

Rochambeau, plus over a thousand animals on hoof and a

similar number of wagons, marched along this route, just

days after Washington and his troops. Rochambeau's troops

camped on the banks of the Schuylkill River (shown by the

yellow boxes), about where 23rd Street is today, between

Race and Locust Streets.

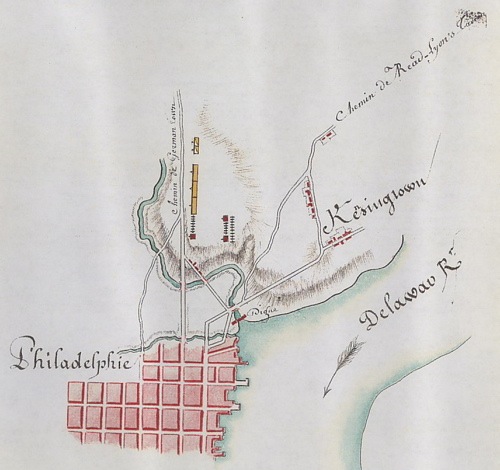

—Detail from

"Twenty-seventh Camp at Philadelphia", MS, 32 x 21 cm,

Princeton University Library, Bethier Papers, No. 39-27,

reproduced in Howard C. Rice Jr., & Anne S. K. Brown

(translators and editors), "The American Campaigns of

Rochambeau's Army, 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783", (Princeton

University Press, 1972).

After the

victory at Yorktown, VA, and the surrender of Cornwallis,

Rochambeau's troops marched north, returning to

Philadelphia on August 31- September 4, 1782.

Rochambeau's troops camped just north of the Cohocksink

Creek, just east of where Second Street and Germantown

Avenue—"Chemin de German Town"—meet (the site

of the recently demolished Schmidt's Brewery). Berthier

shows the main route—"Chemin de Read-Lyons Tavern"

or Road to Red Lion Tavern (fifteen miles north up

Frankford Avenue)— as being the second road after

crossing the Cohocksink.

Note the

"Digue" or dike (in red) across the mouth of the

Cohocksink, below the causeway and bridge. Also note

the small mark to the top right of the "e", shaped

rather like a hot air balloon. This seems to be a

distinctive mark, not a splotch or mistake, and

might denote British Redoubt No. 1

-----

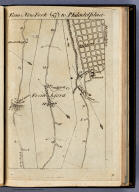

—Detail

"New York to Philadelphia

(1789)", C.

Colles.

The

approach to Philadelphia from New York along Frankford

Road, crossing over the "Cohocksinck Creek" to Front

Street or bend to Second Street. Note the C-shaped

[British] "Barrack" (between today's Second and Third

Streets, Green Street and Fairmount Avenue), and the

"Cho-que-no-quok" or Pegg's Run (today's Willow

Street, just north of Callowhill Street).

-----

"Philadelphia" by Charles P. Varle

(1802).

Two

detailed views from the full map online, c/o David

Rumsey.

Detail showing

the "Entrenchment of the English in the Late War" (dotted

line) and four fortifications (an open square with four

dark squares at the corners) between the Schuylkill River

at Fairmount [Fort No. 10 at the Art Museum] and where

the Cohocksink Creek meets the Delaware River (Reboubt

No. 1 in Kensington).

Detail around

Cohocksink Creek, note the extant fortifications (surely

British Reboubt No. 1), between Frankford Road and

Shackamaxon Street, below "Hall" Street. ("Hall" stood

for the infamous "Batchelor's Hall"). Note also the

"Globe Mills" at top left, the former "Governor's Mill" which was

powered by the Cohocksink.

When the

long stone bridge was built, in 1790, (its date is marked

thereon and done by Souders) they came, at the foot of

the foundation, to several curiosities, described to me

by those who saw them, to wit: —a hickory

hand-cuff, perfectly sound—several leaden weights,

for weighing—a quantity of copper farthings, and a

stone hollowed out like a box, and having a lid of the

same.—John F.

Watson, "Annals of Philadelphia" (1830), pp.

415-420.

Formerly

the Delaware made a great inroad upon the land at the

mouth of the Cohocksinc, making there a large and shallow

bay, extending from Point Pleasant down to Warder's long

wharf, near Green Street. It is but about 30 years since

the river came up daily close to the houses on Front and

Coates' street, and at Coates' street the dock there,

made by Budd's wharfed yard, came up to the line of Front

Street. All the area of the bay (then without the present

street east of Front street, and having none of the

wharves now there) was an immense plane of spatterdocks,

nearly out to the end of Warder's wharf, and on a line to

Point Pleasant. The lower end of Coates' street was then

lower then now; and in freshets the river laid across

Front street. All the ten or twelve houses are north of

Coates' street, on the east side, were built on

made-ground, and their little yards were supported with

wharf-logs, and bush-willows as trees. The then mouth of

Cohocksinc was at a wooden drawbridge, then the only

communication to Kensington, which crossed at Leib's

house opposite to Poplar lane; from thence a raised

causeway ran across to Kensington, was not then in

existence. On the outside of this causeway the river

covered, and spatterdocks grew, and on the inside there

was a great extent of marshy ground alternately wet and

dry, with the ebbing and flowing of the tide; the creek

was embanked on the east side. The marsh was probably 200

feet wide where the causeway at the stone bridge now

runs. The branch of this creek which run up to the Globe

mill, [on the place now used as Craig's cotton

manufactory] was formerly deeper than now. Where it

crosses Second street, at the stone bridge north of

Poplar lane, there was in my time a much lower road, and

the river water, in time of freshets, used to overflow

the low lots on each side of it. The houses near the

causeway, and which were there 30 years ago, are now

buried one story underground. The marsh grounds of

Cohocksinc used to afford good shooting for woodcock and

snipe &c. The road beyond, "being Front street

continued," and the bridge thereon, is all made over this

marsh within the last 16 years; also, the road leading

from the stone bridge across Front to Second

street—the hill, to form that road, has been cut

down full 20-25 feet, and was used to fill up the Front

street causeway to the York road, &c. The region of

country to the north of this place and of Globe mill,

over to Fourth street mill-dam, was formerly all in grass

commons, without scarcely a single house or fence

thereon, and was a very great resort for shooting

kill-dear and snipe. It was said the British had burned

up all the former fences, and for many years afterwards

no attempt was made to try and renew them. On these

commons bullbaiting sometimes occured, and many military

trainings. None of the present ropewalks were then there;

but one run where Poplar lane now lies, from Front to

Second street—that not having been a street til

within 25 years ago. The British redoubts remained til

lately—one on the Delaware bank in a line with the

stone-bridge street—then no houses were near it;

now it is all built up, and streets are run where none

were seen. The next redoubt, west, stood in an open grass

lot of Captain Potts, on Second street and in front of

where St. John's Methodist church now stands.—[John

street was not then run there.] Another redoubt stood on

Poplar lane and corner of Fifth street,—another

back of Bush Hill house, and another was on Fair

Mount,—another on the hill south of High street,

where the waterworks were located. All the Cohocksinc

marsh is now filled up and built upon, and an imense long

wharf and a bridge from it is made to join a street to

Kensington.—John F.

Watson, "Annals of Philadelphia" (1830), pp.

415-420.

-----

—Detail,

"Philadelphia and the commencement of the

road to New York", S.S. Moore & T.W.Jones

(1802)

-----

Painted

in 1800, and supposedly true to life, could the wooden

structure to the right of the famed Treaty Tree (flying

the flag) be the surviving British Redoubt

No.1?

-----

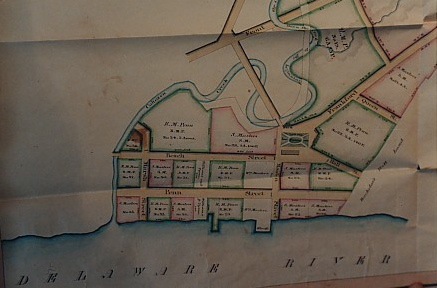

—Detail "Camac

Family Estate Papers,1802-1860" HSP, Call # A39, 4V,

Collection 1420.

Starting in

the early 1700s, the Masters Family purchased about 1,200

acres north of the Cohocksink Creek, including Point

Pleasant. By the early 1800s, the heiresses were Sarah

Masters (the wife of Turner Camac) and Mary Masters (the

wife of Richard Penn, William's grandson). This

watercolor map shows the division of property between

them, with the lots shown as "S. Masters / S. M." and "R.

M. Penn / R. M. P."

Since other maps suggest that British Redoubt No. 1 was

located within the area enclosed by Beach / Hall Street,

Maiden Lane and the Delaware River, a close examination

of the deeds in that small area might reveal a

description and location of British Redoubt No. 1. The

first crossing over the Cohocksink Creek from Northern

Liberties to Kensington was by the causeway and stone

bridge (now Laurel Street). Later, perhaps atop the dike,

a second crossing appeared with a wood

draw-bridge.

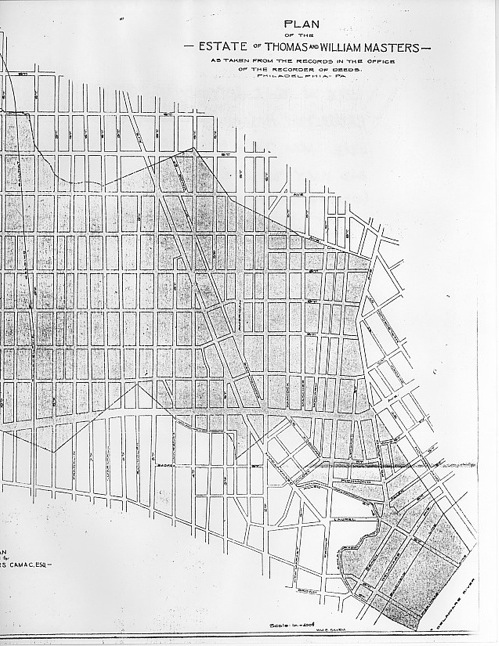

—"Plan of the

Estate of Thomas and William Masters as taken from

the records in the office of the Recorder of Deeds,

Philadelphia."

-----

THE

COHOCKSINK CREEK AND POINT PLEASANT BEFORE 1777.

Surveys and

disputes over property boundaries provide many clues to

the ancient paths of the winding Cohocksink Creek, the

edge of the Delaware River, plus the newly laid-out roads

and buildings around 1730. The Logan Papers at HSP are a

superb resource with over forty surveys and

descriptions. Early deeds

and lawsuits provide additional evidence to help locate

the exact sites of demolished Colonial-era

structures.

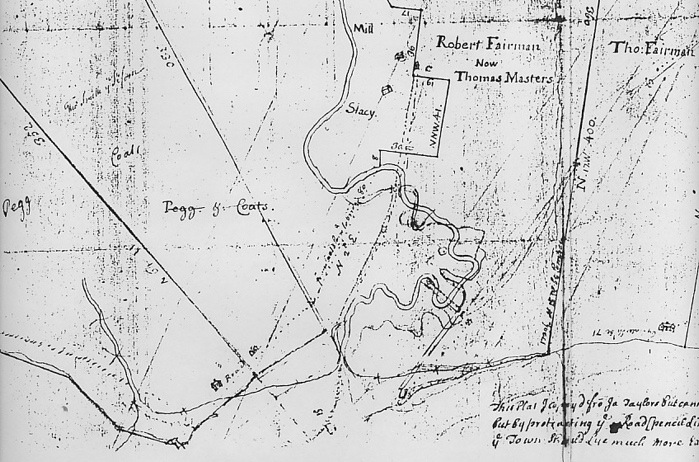

—Partition

of Lands among Fairman Heirs, c. 1714.

Front Street

crosses Pegg's Run before terminating south of the

Cohocksink, where the road to Germantown Road leads up to

Stacy's field and the Mill. John Watson provides superb

details in his "Annals of Philadelphia" (1830), pp.

415-420.

The whole

region was originally patented to Jurian Hartsfelder, in

1676 by Governor Andros of New York government. In ten

years afterwards he sold out to D. Pegg his whole 350

acres, extending from Cohocksinc creek, his northern

line, to Pegg's run, his southern line. That part beyond

Cohocksinc, northward, which came under Penn's patent,

was bought, in 1718, by J. Dickinson—say 945

acres—at 26s. 8d. sterling, and extending from the

present Fairhill estate over to Bush Hill. Part of the

same estate has been known in more modern times as

"Master' estate and farm," and some of it is now in

possession of Turner Camac, Esq. who married Masters'

daughter.

The primitive state of the North End near the Cohocksinc

creek, is expressed in a petition, of the year 1701, of

the country inhabitants (115 in number) of Germantown,

Abington, & c. praying the Governor and Council for a

settled road into the city, and alleging that "they have

lately been obliged to go round new fences, from time to

time set up in the road by Daniel Pegg and Thomas

Sison,"* [* This name was spelt Tison in another place]

for that as they cleared their land, they drove the

travellers out into uneven roads and very dangerous for

carts to pass upon. They therefore pray "a road may be

laid out from the corner of Sison's fence straight over

the creek [meaning the Cohocksinc, and also called

Stacey's creek] to the corner of John Stacey's field, and

afterwards to divide into two branches—one to

Germantown and one to Frankford." They add also that

Germantown road is most travelled—taking thereby

much lime and meal from three mills, with much malt, and

a great deal of wood, timber, &c. At the same time

they notice the site of the present "long stone bridge

and causeway over to Kensington, by saying "they had

measured the road that is called the Frankford road, over

the bridge from about the then part of the tobacco field,

to a broad stone upon Thomas Sison's hill near his fence,

and find it to be 380 perches, and thence to the lower

corner of John Stacey's field to the aforesaid tobacco

field 372 perches, beside (along) the meadow and creeek

by John Stacey's field, and of the latter we had the

disadvantage of the woods, having no line to go by, and

finding a good road all the way and very good fast

lands." I infer from this petition (now in the Logan

collection) that they desired the discontinuance of the

then road over the long bridge to Frankford,** [** It is

possible, however, that the long bridge may have been one

on piles, directly out Front street as it now runs - as

such piles were there in my youth, and a narrow causeway.

It was either the remains of old time, or it had been

made by the British army as they flooded that land.] and

that both Germantown and Frankford roads should diverge

"by as near a road, having fast land all

along."

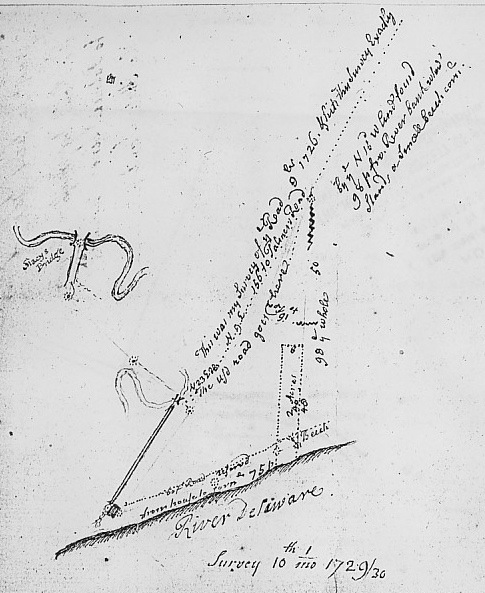

—Survey

10th mo. 1729/30, "I suppose a small part of Frankford

Road near the Bridge... This was my survey of Ye.

Road..." [to Frankford]

—Survey March 10, 1729/30, "[?] to flat part of the

Road by Masters Tide Mill to Palmer's Line including the

Hall Land." [Masters Tide Mill is likely the square

structure near the river]. Source: HSP, Logan's Papers,

Vol 13:41

A letter

of Robert Fairman's, of the 30th of 8 mo. 1711, to

Jonathan Dickinson, speaks of his having a portion of the

13 acres of his land next the Coxon creek (Cohocksinc)

and in Shackamaxo.*** [*** Thus determining, as I

presume, that Shackamaxon began at Cohocksinc creek, and

went up to Gunner's creek.] In another letter of the 12th

of 3 mo. 1715, he says "the old road and the bridge to it

being so decayed and dangerous for passengers, my brother

Thomas, with Thomas Masters, and others thought it proper

to move your court for a new road, which being granted, a

new bridge was made and the road laid out, and timber for

the bridge was cut from my planatation next the creek;

but not being finished before my brother Thomas died, has

since been laid aside and the old bridge and road are

repaired and used—thus cutting through that land of

mine and his, so as to leave it common and open to

cattle, & c. notwithstanding the new road would have

been a better route. This has proceeded from the malice

of some who were piqued at my

brother."

In the

year 1713, the Grand Jury, upon an inspection of the

state of the causeway and bridge over the Cohocksinc, on

the road leading to the "Governor's mill"—where is

now Craig's manufactory—recommend that a tax of one

pence per pound be laid "to repair the road at the new

bridge by the Governor's mill, and for other purposes."

In 1739 the said mill took fire and was burnt down. It

was thought it occured from the wadding of guns fired at

wild pigeons.

This mill seems to have been all along an ill adventure;

for James Logan, in 1702, speaking of the Governor's two

mills, says, "those unhappy expensive mills have costs

since his departure upwards of 200 in dry money. They

both go these ten days. The "Town Mill," (now Craig's

place) after throwing away 150£. upon her, does exceeding

well, and of a small one is equal to any in the

province."

Old Mr. Wager (the father of the present Wagers) and

Major Kisell have both declared, that as much as 60-65

years ago they had seen small vessels with falling masts

go up the Cohocksinc creek with grain, to the Globe

mill—the same befoe called the Governor's mill. Old

Captain Potts, who lived near there, told me the same

thing when I was a boy. —John F.

Watson, "Annals of Philadelphia" (1830), pp.

415-420.

—Detail of survey c.

1729 showing Fairhill. —Source: HSP, Logan's

Papers, Vol 13:41

The Fairhill

estate of Isaac Norris was over 800 acres, from the north

bank of the Aramingo Creek towards the "mansion" [shown

near the center of the image and below] which stood near

today's 6th & York Streets. Philadelphia is the

rectangle to the left with ten houses along the Delaware

River. Pegg's Run is just north of the city line. Dotted

lines signify Front Street, splitting at the Cohocksink

Creek towards Germantown and Frankford [shown at right].

Ridge Avenue heads towards the mouth of the Wissahickon

and the "Robinson" mill [at top].

A superb, extensive and

illustrated description of "Isaac Norris's Fairhill" by

Mark Reinberger and Elizabeth McLean was published in

Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 32, No. 4, Winter 1997, pp.

243-274.

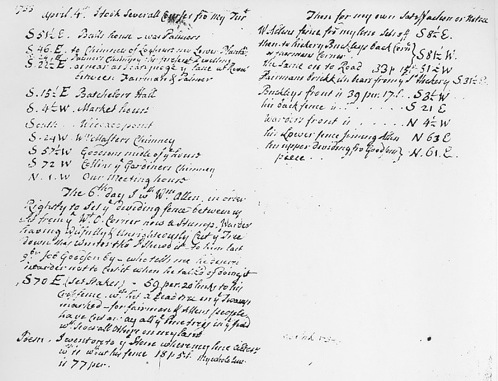

"1733, April 4th, I took

severall courses from my Tur" [turret atop

Fairhill].—Source: HSP,

Logan's Papers, Vol 13:48½

From his roof,

the learned Isaac Norris took directions to surrounding

landmarks:

S 51½ E. Balls house - was Palmers [also known as

Richmond Hall, between the Aramingo Creek and the

Delaware River. Palmer sold this in 1729 and bought 191½

acres from the Fairman estate to found "Kensington"]

S 24 E. Palmers Chimney [?] the present dwelling or near

as I can ...

S 15½ E. Batchelor's Hall [which stood near the foot of

Shackamaxon Street near the Delaware River].

S 4½ E. Market House [likely Second and Market Streets,

Philadelphia].

S 24 W. Wm. Masters Chimney

...

-----

The

Cohocksink Creek as canal and sewer.

—Detail from

birds eye view, "Philadelphia in

1888", Burk &

McFetridge (source: Library of

Congress)

The beginning

of the Cohocksink Canal can be seen as the winding red

line. Sugar House sits on the riverside of the parallel

red train tracks, under the red #19.

-----

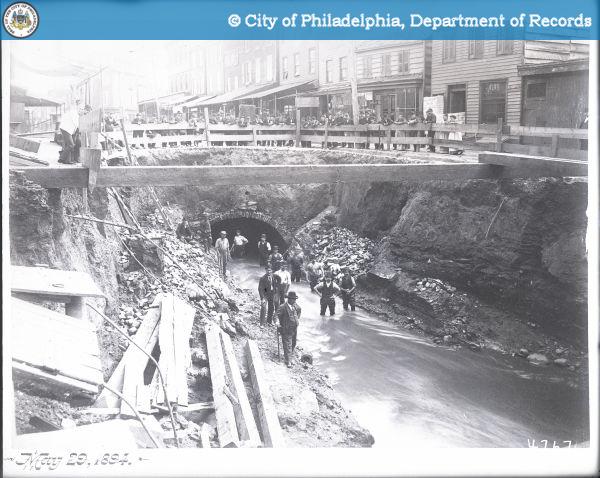

—Break In Cohocksink Sewer - Germantown

Avenue Above 2nd Street [below

Girard].

Construction Of Cohocksink Sewer. (May 29, 1894).

Source: Philadelphia Archives /

PhillyHistory.org

Inspectors from the Philadelphia Water Department say the

Cohocksink Sewer below Girard Avenue approaches twelve

feet in diameter, which seems close to accurate from this

photo.

-----

RESOURCES

(books, manuscripts, maps, surveys,

texts)

BOOKS

William

Howe, "The Narrative of Lieut. Gen. Sir William Howe...

(Baldwin, London, 1780), pp. 54-55.

John

W. Jackson, "With the British Army in Philadelphia

1777-1778" (Presidio, 1979).

Philip Chadwick Foster Smith, "Philadelphia on the River"

(Philadelphia Maritime Museum, 1986).

David Breckenridge Read, "The Life and Times of Gen. John Graves

Simcoe, Commander of the 'Queen's Rangers' during the

Revolutionary War, and first Governor of Upper

Canada" (George

Virtue, Toronto, 1890).

Harry M.

Lydenberg, Editor, "Archibald

Robertson, Lt. General, Royal Engineers: His Diaries and

Sketches in America, 1762-1780," (New

York, 1930) [Robertson's original drawings and diary are

in the Spencer Collection of the New York Public

Library].

G.D. Scull, editor, The Journals of Capt. John

Montresor from the

original manuscript in the possession of the Montresor

family (Collections of the New York Historical

Society, 1881).

Lieutenant-Colonel John Graves Simcoe, "A Journal of the

operations of the Queens Rangers, from the end of the

Year 1777 to the Conclusion of the late American War"

(Exeter, printed for the author, 1782?).

Lieutenant-Colonel John Graves Simcoe,

"Military Journal—A History of the

Partisan Corps called the Queens Rangers, Commanded b

y Lieut. Col. J.G. Simcoe, during the War of the

American Revolution", (New

York, 1844).

"Excerpts from the Journal of Lieut. Col.

John G. Simcoe and the Queen's Rangers in

Revolutionary Kensington"

Frank E. Snyder & Brian H. Gus, "The District, A

History of the Philadelphia District U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers, 1866-1971 (U.S. Army Engineer District,

Philadelphia, 1971), pp. 106-115 & pp. 156-157.

Martin P. Snyder, "City of Independence—Views of

Philadelphia Before 1800" (Praeger, New York, 1975).

Frank H. Taylor, "Valley Forge, A Chronicle of American

Heroism" (Nagle,

1905, 1911, +), see items "The British Army in

Philadelphia" &

"Country Seats

Destroyed."

Russell F. Weigley (Editor), "Philadelphia, A 300-Year

History" (Norton, New York, 1982), especially pp. 138-139

with related footnotes. "The whole tedious business of

gaining control of the Delaware left the British army

feeling far less at ease in Philadelphia than they had

anticipated. To ward off another attack by Washington,

Howe erected a chain of ten redoubts, with connecting

abatis, between the iwo rivers in a line running of and

parallel to Callowhill Street. The construction of these

works, begun while Howe was still in Germantown, was

hampered by a labor shortage. Although Joseph Galloway

was sure it would be a simple matter to get 500 civilians

to do the digging, the most the British could obtain was

about eighty. Few were interested in working all day for

eight pence and a ration of salt provisions. Many summer

mansions that might have sheltered snipers along

the defense line were burned to the ground, including

John Dickinson's Fair Hill, formerly a residence of his

father-in-law Isaac Norris II."

Edwin Wolf, 2nd, "Philadelphia, Portrait of an American

City" (Stackpole, Harrisburg, PA, 1975).

MAPS

showing the area around Point Pleasant, including the

defenses built by the British in 1777 to defend

Philadelphia.

— "A survey of the city of Philadelphia and

its environs shewing the several works constructed by

His Majesty's troops, under the command of Sir William

Howe, since their possession of that city 26th.

September 1777, comprehending likewise the attacks

against Fort Mifflin on Mud Island, and until it's

reduction, 16th November 1777. Surveyed & drawn by

P. Nicole. Anotated: John Montresor, chief

engineer." Collection:

Library of Congress.

— "A survey of the city of Philadelphia and

its environs shewing the several works constructed by

His Majesty's troops, under the command of Sir William

Howe, since their possession of that city 26th.

September 1777, comprehending likewise the attacks

against Fort Mifflin on Mud Island, and until it's

reduction, 16th November 1777. Surveyed & drawn by

P. Nicole. Anotated: John Montresor, chief

engineer." Collection:

Library of Congress.

— A Survey

of the City of Philadelphia & it's Environs

comprehending the Neck formed by the Rivers of

Delaware & Schuylkill; together with Province,

Carpenters, & Mud Islands, & the several

Batteries & Works constructed thereon.

Philadelphia 15th Dec. 1777, John Montresor Chief

Engineer, 31-7/8" x 27-3/8", at the British Museum.

[Reproduced in Martin P. Snyder, "City of

Independence—Views of Philadelphia Before

1800" (Praeger, New York, 1975), pp. 116-119.]

— A Survey

of the City of Philadelphia & it's Environs

comprehending the Neck formed by the Rivers of

Delaware & Schuylkill; together with Province,

Carpenters, & Mud Islands, & the several

Batteries & Works constructed thereon.

Philadelphia 15th Dec. 1777, John Montresor Chief

Engineer, 31-7/8" x 27-3/8", at the British Museum.

[Reproduced in Martin P. Snyder, "City of

Independence—Views of Philadelphia Before

1800" (Praeger, New York, 1975), pp. 116-119.]

To His Excellency, Sir Henry Clinton K. B. General and

Commander in Chief of his Majesty's Forces, within the

Colonies laying on the Atlantic Ocean from Nova Scotia to

West Florida inclusive &c. &c. &c. John

Montresor Chief Engineer, 26-1/4" x 38-3/4", at the

University of Michigan William L. Clements Library,

Clinton Papers, described in Randolph G. Adams, British

Headquarters Maps and Sketches (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1928),

pp. 77-78.

Untitled plan of Philadelphia, 35-1/4" x 27-3/4, at the

William L. Clements Library, described in above, p. 77.

Untitled plan of roads leading out of the city, 12-1/2" x

15-3/4", at Library of Congress, described in P. Lee

Phillips, A Descriptive List of Maps and Views of

Philadelphia in the Library of Congress, no. 170.

Plans of British Army positions within present-day

Philadelphia, by John Andre, at the Huntington Library,

San Marino, California, reproduced in

Henry Cabot Lodge, ed., "Major Andre's Journal" (Boston,

1903), I:124, 128, 132, 134.

Untitled plan of a British camp on the Schuylkill River,

by Sir Henry Clinton, at the William L. Clements Library,

described in Randolph G. Adams, British Headquarters Maps

and Sketches (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1928), p. 78.

— From New York To Philadelphia

(1789),

Christopher Colles

— From New York To Philadelphia

(1789),

Christopher Colles

—Charles P. Varle, Philadelphia

(1802). "To The

Citizens Of Philadelphia This New Plan Of The City And

Its Environs Is respectfully dedicated By the Editor.

1802. P.C. Varle Geographer & Enginr. "A

beautiful, early map of Philadelphia in full period

color. The scale is given at 75 Perches to 1 inch. The

city is shown from the Delaware River to the Schuylkil

River with the environs on the north and south. 24

lettered references and 28 numbered references to

important places and buildings are below the title and

24 wards are keyed in Roman numbers above the title.

Many of the country houses and farms around the city

are named, including Penn, Dr. Wistar, and other

notable early residents. Three inset views show City

Hall, the State House, Court House, Library, and Bank

of the United States. The tile is surrounded by a

decorative cartouche. The quality of the engraving is

superb. Ristow mentions an undated edition that was

possibly issued in the year Varle made the surveys,

1796, but more likely in 1802. Wheat and Brun list a

c.1794 State I that has one less numbered building

reference, no Roman numbered ward references, and ""R.

Scott Sculp. Philadelphia."" This was Varle's first

map published in the United States. Until 1807, Varle

was known as Peter C. Varle; after 1807 he is known as

Charles P. Varle." —davidrumsey.com

—Charles P. Varle, Philadelphia

(1802). "To The

Citizens Of Philadelphia This New Plan Of The City And

Its Environs Is respectfully dedicated By the Editor.

1802. P.C. Varle Geographer & Enginr. "A

beautiful, early map of Philadelphia in full period

color. The scale is given at 75 Perches to 1 inch. The

city is shown from the Delaware River to the Schuylkil

River with the environs on the north and south. 24

lettered references and 28 numbered references to

important places and buildings are below the title and

24 wards are keyed in Roman numbers above the title.

Many of the country houses and farms around the city

are named, including Penn, Dr. Wistar, and other

notable early residents. Three inset views show City

Hall, the State House, Court House, Library, and Bank

of the United States. The tile is surrounded by a

decorative cartouche. The quality of the engraving is

superb. Ristow mentions an undated edition that was

possibly issued in the year Varle made the surveys,

1796, but more likely in 1802. Wheat and Brun list a

c.1794 State I that has one less numbered building

reference, no Roman numbered ward references, and ""R.

Scott Sculp. Philadelphia."" This was Varle's first

map published in the United States. Until 1807, Varle

was known as Peter C. Varle; after 1807 he is known as

Charles P. Varle." —davidrumsey.com

— Philadelphia and the commencement of the

road to New York (1802), S.S. Moore & T.W.

Jones

— Philadelphia and the commencement of the

road to New York (1802), S.S. Moore & T.W.

Jones